275th Anniversary: Fr. Barrière

The Vidrine Family in LA celebrates the 275th anniversary of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ departure from France and arrival of LA in 2018. It’s a great time to remember and reflect on the 275 years of history of his descendants and the life and family he established in LA as well as the people involved in or related to the family.

We saw in the last reflection about the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge that as the Védrines Family moved west of the Opelousas Post and was literally becoming the Vidrine Family – as the two progenitors in LA passed on and their children, the second generation, took the helm – Fr. Michel Barrière was present to them as a sort of bridge linking the old and the new. His life – one of the greatest Apostles of Southwest Louisiana’s Bayous and Prairies – is a very interesting one. And it’s important to the Védrines-Vidrine Family not only because Fr. Barrière was their Pastor of the Opelousas Post who baptized, married, anointed, and buried the Vidrine pioneers and their children – but also because of his personal knowledge for many years of this same family in France, which he himself noted.

Michel Bernard Barrière was born in the parish of Saint Mexant in Bordeaux, France on May 30, 1755 and baptized the same day in the Cathedral Saint André (Rev. Donald Hebert, Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 17, Nov. 1997, p.3). He appears to be named after his maternal grandfather, Michel Bernard, who served as his godfather. Michel Barrière was the second child of François Barrière and Françoise Rose Bernard. His father was a clerk of the Table de Marbre, the office in Bordeaux’s Parliament which had jurisdiction over the waters and forests, and his grandfather was the chief clerk. He had an older sister named Catherine and would later have seven younger brothers and sisters. One was named Michel, born in 1761, with Fr. Barrière serving as his godfather, who would eventually join his brother in Louisiana (Rev. Donald Hebert, Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 17, Nov. 1997, p.3).

Perhaps Fr. Barrière’s family had a greater influence than they could have imagined. It is difficult not to see the connection between him being the son and grandson of the clerk of the courts of the Parliament of Bordeaux and his amazing work he would later undertake to maintain the sacramental records of the parishes of Attakapas and Opelousas in Louisiana. As Fr. Donald Hebert noted:

“Fr. Barrière was a real friend to the genealogist and historical researcher. He never realized that many years after he died, there would be people like ourselves who would appreciate the exactitude and completeness with which he recorded the every-day events of church and sacramental life for his flock” (Rev. Donald Hebert, Southwest Louisiana Records V.2A, Rayne, LA: Hebert Publications, 1997, p. 35).

This is true in particular for the Vidrine Family.

Fr. Barrière was ordained to the Priesthood at the Cathedral of St John the Baptist in Bazas, France in May of 1782 (Claude Massé, Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 15,  Jul. 1996, p.15). A few years after his Priestly ordination, he was assigned in February 1785 as the assistant chaplain at L’Hôpital de la Manufacture or Foundling Hospital (Home for Abandoned Children) in Bordeaux. The archives of the Home which have survived the chaos of the Revolution are often not helpful and can even be deceiving. But they do help us in this case as they provide some evidence of Fr. Barrière’s ministry as the assistant chaplain at the Home.

Jul. 1996, p.15). A few years after his Priestly ordination, he was assigned in February 1785 as the assistant chaplain at L’Hôpital de la Manufacture or Foundling Hospital (Home for Abandoned Children) in Bordeaux. The archives of the Home which have survived the chaos of the Revolution are often not helpful and can even be deceiving. But they do help us in this case as they provide some evidence of Fr. Barrière’s ministry as the assistant chaplain at the Home.

In the files of the Treasurer which have been preserved, there are seven receipts written and signed by Fr. Barrière for his salary from February 1785 to January 1788. And since the minutes of the meetings of the administration between 1784 and 1791 do not mention a change in the position of the assistant chaplain, he seems to have had those duties at the Home until the last staff meeting on March 13, 1791, when the persecution of the Revolution in Bordeaux began (Claude Massé, Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 15, Jul. 1996, p.16).

On Sunday, February 6, 1791, the Municipality of Bordeaux revealed a significant decision regarding the chaplains of the various Homes dedicated to charity. Since their life and ministry were considered public functions, all chaplains were required to take the oath to the Nation; if they refused, they had to be removed and replaced (Claude Massé, Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 15, Jul. 1996, p. 16). The head chaplain at the Home for Abandoned Children in Bordeaux, Abbé Audureau, declared that he would never take the oath. From Fr. Michel Barrière’s notes written later in the registers of his parish in Louisiana, we know that he also refused. Discussion about the consequences for the refusal to sign the oath continued in the months that followed, but it became clear that the two chaplains would face them (Claude Massé, Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 15, Jul. 1996, p.17).

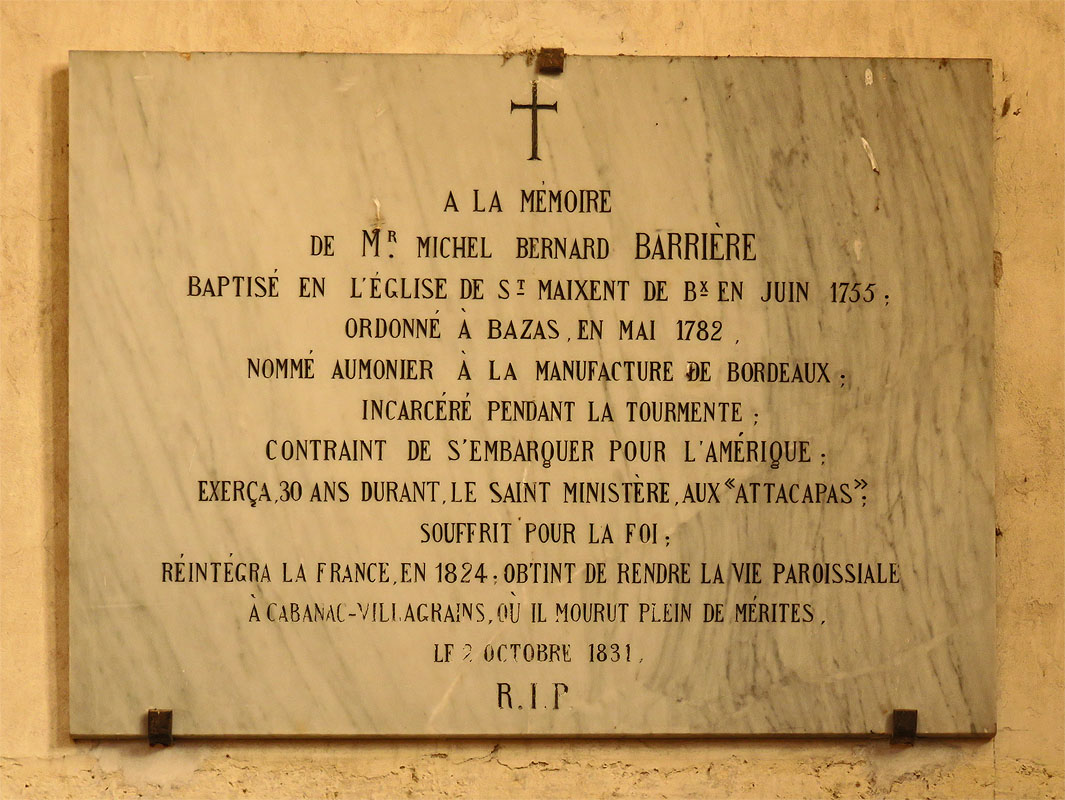

As the Revolution progressed, Priests who refused to sign the oath suffered the consequences imposed by the State, especially in Bordeaux. They were jailed in great numbers – no doubt in appalling conditions – as well as deported. But in the long list of Priests who were put in jail, Fr. Michel Barrière’s name is not found (Claude Massé, Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 15, Jul. 1996, p.18). Even still, according to the memorial plaque at the church of Cabanac, Abbé Barrière was imprisoned during the Revolution and deported to America. Fr. Spalding claimed that he escaped from a prison in Bordeaux and chose to flee the Revolution in France, sailing from the port of Bordeaux to America (Rev. M.J. Spalding, Sketches of the Early Catholic Missions of Kentucky, Louisville: B.J. Webb and Brother, 1844, p.63). Others have speculated that he may have even done so clandestinely (see Claude Massé, Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 15, Jul. 1996, p.19).

Fr. Barrière himself made a note in the Baptismal register of St. Landry Church in  Opelousas, LA, where he briefly mentions his departure. In the note, he wrote about both “fleeing” “the horrors of anarchy” as well as being “expelled from our country”. So even he doesn’t seem to clarify the way he departed France. But whether he was imprisoned and deported or freely chose to flee France, it must have happened very quickly because at the beginning of the Fall of 1793, Fr. Barrière was already in Baltimore, Maryland.

Opelousas, LA, where he briefly mentions his departure. In the note, he wrote about both “fleeing” “the horrors of anarchy” as well as being “expelled from our country”. So even he doesn’t seem to clarify the way he departed France. But whether he was imprisoned and deported or freely chose to flee France, it must have happened very quickly because at the beginning of the Fall of 1793, Fr. Barrière was already in Baltimore, Maryland.

The anarchy of the Revolution indeed arrived, and the mortality rate rose very quickly. Abbé Audureau, the head chaplain of the Home for Abandoned Children, was imprisoned and died on December 4, 1794 at the Blaye hospital. Other Priests died the same day, one of them with Fr. Audureau at the Blaye hospital and others at the Saint-André hospital in Bordeaux. During the course of 1794, one hundred sixty-seven Priests in Bordeaux refused to swear the oath, and most of them died during the last six months of that year, either at Saint-André hospital or the Blaye hospital if not by the Guillotine (Claude Massé, Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 15, Jul. 1996, p.18).

Whether Fr. Barrière had been deported or freely chose to become an émigré Priest is not known for sure. But while many of his colleagues were suffering martyrdom, he was on a ship to America (See note about passport, Jacqueline Vidrine, Vedrines-Vidrine, Lafayette, LA: Acadiana Press, 1981, p.155). Indeed, the number of Priests who died during the French Revolution would’ve been much more if so many of them had not immigrated; some estimate that as many as forty thousand did. Their refusal to compromise with the Revolution was a great act of virtue, and therefore, commendable. Immigration was certainly an easier option than the persecution of the Revolution. But at the same time, fleeing France involved many sacrifices, both spiritual and physical. Many of the clergy were totally destitute when they finally reached the countries which they hoped would receive them.

Surprisingly, a good number of the émigré clergy decided to make the two to three month journey to the new world across the ocean. Distraught by the new regime and fearing either execution or a different way of life they didn’t want, many Priests were part of the nearly ten thousand who braved the dangers and difficulties of travel across the Atlantic during the last decade of the Eighteenth century (Thomas C. Sosnowski, A “Noble” Attraction: French Revolutionary Exiles in the Trans-Appalachian West, p.31 in Ohio Academy of History Proceedings, http://www.ohioacademyofhistory.org).

Either deported as a punishment or personally chosen to escape the Terror of the Revolution, Fr. Barrière found himself – as one of the émigré clergy – in the new world. He arrived in Baltimore during the summer of 1793. Bishop Carroll welcomed him and by that September, sent him to Kentucky as Vicar General for the missionary territories. Sent with him was another native of France and fellow émigré, Fr. Stephen Theodore Badin, who had just been ordained on May 25, 1793 – the first Catholic Priest ordained in the United States.

The two missionary Priests left Baltimore on September 6, 1793, and after an incredibly  difficult journey on foot over the Appalachian Mountains, down terrible roads and through rough country, they arrived at Pittsburgh. Then, on November 3, they boarded a flatboat heading south down the Ohio River (See Camillus Maes, “Stephen Theodore Badin”, The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02200b.htm).

difficult journey on foot over the Appalachian Mountains, down terrible roads and through rough country, they arrived at Pittsburgh. Then, on November 3, they boarded a flatboat heading south down the Ohio River (See Camillus Maes, “Stephen Theodore Badin”, The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02200b.htm).

After seven days of travel, they arrived at Gallipolis where most of the residents were French Catholics who had been without a Pastor for a long time (See Lawrence J. Kenny, S.J.: The Gallipolis Colony (1790), in The Catholic Historical Review. Vol. IV, No. 4 January 1819, pp. 415-451). During their three days at Gallipolis, they sang a High Mass in the garrison and baptized forty children. The French colonists were so delighted to have the Priests in their village that the tears flowed as they were leaving (Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M, Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.244).

They landed next at Maysville, where there were about twenty families. Having spent the first night in an open mill six miles from Limestone, sleeping on the mill bags, with no covering, during a cold night late in November, they then walked about sixty five miles to Lexington (Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M, Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.245).

They arrived in Lexington on December 1, 1793 – the first Sunday of Advent. Fr. Badin offered Holy Mass for the first time in Kentucky there, in the house of Mr. Dennis McCarthy. Then traveling sixteen more miles that same day until he reached the Catholic settlement of Bardstown, he brought their only chalice to Fr. Barrière who offered Holy Mass at White Sulphur (See Camillus Maes, “Stephen Theodore Badin”, The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02200b.htm; See also A History of Kentucky and Kentuckians, Volume 1, E. Polk Johnson, p. 458).

Fr. Badin remained in Scott County for about eighteen months, visiting the various Catholic settlements in Kentucky while Fr. Barrière served the Catholic families around Bardstown. They would travel from mission to mission on horseback every day to visit their flock and minister to the sick (Margaret DePalma, Dialogue on the Frontier: Catholic and Protestant Relations, 1793-1883, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2004, p.29). Before long, though, Fr. Barrière found the mission in the backwoods of Kentucky too difficult, and particularly the English language (Rev Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.245). So about four months after his arrival in Kentucky, he left Louisville in April of 1794 in a pirogue and headed south down the Mississippi. Bishop Carroll later expressed great disappointment that Fr. Barrière left the English settlements he had sent him to serve so soon after he arrived (John Dichtl, Frontiers of Faith: Bringing Catholicism to the West in the Early Republic, Louisville: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008, p.37). Likewise, Fr. Badin lamented that he had been left alone as a novice in the missions (Margaret DePalma, Dialogue on the Frontier: Catholic and Protestant Relations, 1793-1883, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2004, p.29). But with great missionary zeal, Fr. Barrière headed for New Orleans where he knew he could better serve those who spoke his native French (Camillus Maes, “Stephen Theodore Badin”, The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2, New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907).

Since the Spanish government was now in control of Lower Louisiana, it was on guard for an attack by the French. Being a native of France, Fr. Barrière was arrested and detained in southern Missouri. He wrote to the Spanish Governor of Louisiana explaining why he was going to New Orleans and was released and allowed to continue down the Mississippi (Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.245). Fr. Barrière arrived safely in New Orleans on October 16, 1794 and on January 19 1795, was appointed Pastor of the Attakapas Post where he would minister zealously for three decades in the missionary territories.

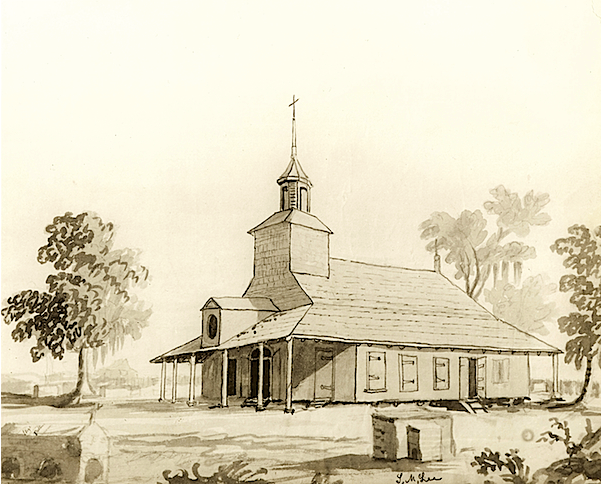

Arriving at Attakapas, Fr. Barrière claimed the Post of St. Martinville as his headquarters.  Like he had done during his few months in Kentucky, he visited the homes of his parishioners throughout the whole area around the Attakapas Post (to nearly every part of what is today the Diocese of Lafayette), including areas not yet developed. It seems that for his normal route, he crossed the bayou between Breaux Bridge and Carencro, then went south and crossed the Vermilion again just south of present-day Lafayette, and then crossed the Cote Gelee to return home. Of course, at other times he traveled a different way. But one thing was sure: when he returned to St. Martinville, he always recorded the sacraments he celebrated during his missionary journeys in the parish’s registers (The Church of the Attakapas, 1750-1889, America Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. xiv, 1889, pp. 462-487).

Like he had done during his few months in Kentucky, he visited the homes of his parishioners throughout the whole area around the Attakapas Post (to nearly every part of what is today the Diocese of Lafayette), including areas not yet developed. It seems that for his normal route, he crossed the bayou between Breaux Bridge and Carencro, then went south and crossed the Vermilion again just south of present-day Lafayette, and then crossed the Cote Gelee to return home. Of course, at other times he traveled a different way. But one thing was sure: when he returned to St. Martinville, he always recorded the sacraments he celebrated during his missionary journeys in the parish’s registers (The Church of the Attakapas, 1750-1889, America Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. xiv, 1889, pp. 462-487).

Tracing his paths, Fr. Souvay gives us a glimpse of Fr. Barrière’s missionary zeal:

“From the testimony of the Church Registers of St. Martin, it appears that during the time of his incumbency at the latter place (March 8, 1795 to October 1804), Father Barrière

visited this neighborhood some fifteen times. These little salidas – to use his own expression – took him habitually three or four days. His customary stations were, about the site of the modern village of Carencro, at Mrs. Arcenaux and Pierre Hebert’s, although we find him occasionally stopping with Pierre Bernard, Francois Caramouche, Joseph Mire, Joseph Breaux and, in 1804, Frederic Mouton. Farther south, at the Grande Prairie, Father Barrière found the large plantation of Jean Mouton “T’oncle, dit Chapeau”, where he never failed to go; once in a while we meet him also at the house of Marin Mouton, Jean’s brother, of Anselme Thibodeaux, Don Nicolas Rousseau, Joseph Hebert, Louis Trahan and Pierre Trahan. Still farther down along the Bayou, he sometimes visited Mrs. Daygle and the Landrys, whilst on the Cote Gelee he was twice the guest of Don Jean Baptiste Broussard and once of Jean Baptiste Comeaux” (Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.246).

And as Fr. Souvay points out, it didn’t stop there:

“And should anyone be tempted to think that his pastoral visits to these quarters were too rare and far apart, let him bethink himself that the good man had, besides his flock of St. Martin and along the Vermillion, “other sheep that were not of this fold”. The territory under his spiritual care was immense, and we see him once in a while saddle his horse for trips down the “Baillou Tech,” as he writes, the Prairie St. Jacques, la Cote des Anglais, la Prairie Salee, la Cote des Allemands, and returning by way of New Iberia (already in existence and known by that name), where he stopped at the house of Joseph Saingermain, a native of Fort de Chartres, Illinois. At other times he had to direct his course down the Bayou Vermillion, or yet en el parage de la Punta, as he puts it, where he assembled the scattered Catholics of the neighborhood in the habitation of Mrs. Claude Martin” (Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.246).

Through these missionary journeys, a conclusion can be made about Fr. Barrière. He was both a good man who lived a simple life as well as an unselfish, pious, and zealous Priest who was loved by those he served. His sincere interest in and love for his parish is captured genuinely in the records that he helped to preserve from his predecessors as well as those which he himself kept so well.

In 1805, Fr. Barrière was replaced as Pastor of the parish of St. Martin by Fr. Isabey. He remained in residence at St. Martinville, keeping the title of “Prêtre approuvé pour tout le Diocese” (Priest approved for the whole Diocese). There, he occasionally lent a helping hand to his successor and even continued the practice of his occasional salidas to the outlying areas (Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.246). For example, on March 31, 1812, he celebrated the marriage “au quartier du Carencros,” of Jean Baptiste Benoit of Opelousas and Helene Roger, of Carencro. He went back one week later – “sent by Father Isabey” (as the note in the register is sure to point out) – for the marriage of Joseph Hebert and Justine Guilbeau; and just a few months later, he was “au Vermilion,” witnessing the marriage of Joseph Guedry and Marie Comeaux (Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.246).

While in residence at St. Martin, there was one particular instance when all of his faithful missionary works were almost crowned with martyrdom. As he was travelling around Lake Chitimacha, he met up with a group of hostile Indians by surprise, and they were more than ready to torture him and put him to death. They had already wrenched the nails off his fingers and toes when the head of the tribe arrived. He surprisingly protected the missionary, commanded that the torture be stopped immediately, and took care of him, making sure he returned safely to his home on the Teche. And so once again, Fr. Barrière showed his great humility and modesty by neither recording anything about this heroic struggle for the faith nor alluding to it in the many notes he made in the pages of his church registers (Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.251).

In 1813, Fr. Barrière was moved a little further north where he was put “in charge of the  parish of Opelousas”. Even though he was now older, he could still saddle his horse for his missionary journeys throughout his parish, and these still occasionally presented extreme difficulties. Fr. Barrière makes the note that while one of his parishioners on the prairie was dying, “he could not receive the sacraments due to the high water which flooded everywhere because of the abundant rains which we’ve received for over a month and the lack of bridges. (See St. Landry Church (Opelousas, LA), Death Register, V.1, p.138).

parish of Opelousas”. Even though he was now older, he could still saddle his horse for his missionary journeys throughout his parish, and these still occasionally presented extreme difficulties. Fr. Barrière makes the note that while one of his parishioners on the prairie was dying, “he could not receive the sacraments due to the high water which flooded everywhere because of the abundant rains which we’ve received for over a month and the lack of bridges. (See St. Landry Church (Opelousas, LA), Death Register, V.1, p.138).

According to the Baptismal records, Fr. Barrière took a missionary excursion toward the middle of November 1813, celebrating at least eighteen baptisms. Though by this point he was no longer young, he traveled through the “Prairie Mamou,” to James Campbell’s, then to Mrs. Hall’s, then again to Dennis McDaniel’s at the head of “Bayou Chicot”, then to the “quartier called Baton Rouge” at the house of “Mr. [Jean] Baptiste de Vidrinne” (on the outskirts of Prairie Mamou, in present-day Ville Platte), and finally at Pierre Foret’s, in the “Prairie Ronde. » (Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, (St. Louis, MO: 1920), p.246).

We know for sure that Fr. Barrière was at the home of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine on November 18, 1813. As he notes in the Sacramental Records, it was during a mission “Dans le quartier dit du Baton Rouge chez Mr. Baptiste de Vidrinne” [in the area called Baton Rouge at Mr. Baptiste de Vidrinne] on November 18, 1813 that he baptized Celeste McDonald (daughter of John McDaniel, Sr. and Catherine Corkran), Damasena Ortego (daughter of Jean Francois Ortego and Eugenie Fontenau), and Margarita Ortego (daughter of Joseph Gregoire Ortego and Emelie Fontenau). During this same time, Fr. Barrière encountered the matron of the Vidrine family in Louisiana, Elisabeth de Monchervaux, who was now living with and receiving care during her sickness from her son Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine at the Quartier dit Baton Rouge.

We don’t know if Fr. Barrière went on another Mission throughout the parish and to the home of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine two years later, but on the same day, – November 8, 1815, he baptized Andre Vidrine, son of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine and Marie-Josephe Brignac and Victoire Irene Lapaise Vidrine, daughter of Etienne Vidrine dit Lapaise and Victoire Soileau.

The following summer, he would be gathered again with the Vidrine Family as he witnessed the marriage of Pierre Vidrine Jr. [son of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine and Marie-Josephe Brignac] and Adelaide Larose Fontenot on May 14, 1816.

Later that fall, he would have the entire Vidrine Family in LA before him as he buried Elisabeth de Moncharvaux – wife of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Vedrines and matriarch of all Vidrines in LA – on September 7, 1816. Fr. Barrière notes in the record of her death and burial that she spent “three long years” at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge before dying there.

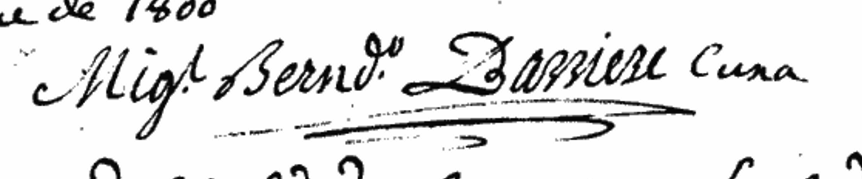

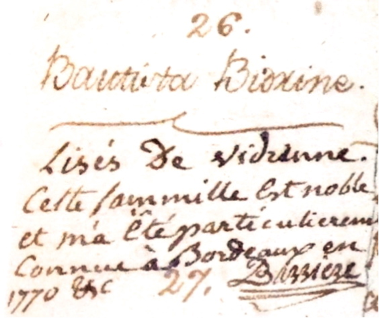

It’s not surprising that Fr. Barrière was at the home of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine where he celebrated the Sacraments on his missionary journey through the Opelousas Prairie considering an interesting note he made in the Sacramental records. As was stated, he is well known for his various notes in the margins of the Sacramental records, in which he  expressed strong memories and feelings as he went through the parish records. In the first Baptismal register of St. Landry Church, there’s a note made in the margin next to the entry about Jean Pierre Baptiste Vidrine’s second son, Lisandre Jean Baptiste Vidrine, who had been baptized by Fr. Pedro de Zamora in August of 1791. The Spanish Capuchin had recorded the name as he had most likely heard it – incorrectly – as Bidrine. When he went through the registers as the Pastor years later, Fr. Barrière corrected it by noting that it was actually de Vidrenne (Védrines), and that he had known the family well in Bordeaux in 1770.

expressed strong memories and feelings as he went through the parish records. In the first Baptismal register of St. Landry Church, there’s a note made in the margin next to the entry about Jean Pierre Baptiste Vidrine’s second son, Lisandre Jean Baptiste Vidrine, who had been baptized by Fr. Pedro de Zamora in August of 1791. The Spanish Capuchin had recorded the name as he had most likely heard it – incorrectly – as Bidrine. When he went through the registers as the Pastor years later, Fr. Barrière corrected it by noting that it was actually de Vidrenne (Védrines), and that he had known the family well in Bordeaux in 1770.

It is not clear how he knew the Védrines family in Bordeaux. He could have known the brothers of Jean Baptiste Lepaise de Védrines who remained in the Bordeaux region of France. One of them, in particular, Guillaume de Védrines, was a Benedictine monk at the Abbaye de Sainte-Croix in Bordeaux, France. By 1767, Fr. Guillaume was serving as Sub-Prior of the Abbey of Sainte-Croix. In 1770 – the year that Fr. Barrière said he knew the Védrines family well in Bordeaux – he was 15 years old. Did he and his family attend Holy Mass at Sainte-Croix? Fr. Barrière was ordained a Priest in 1782 and by February of 1785, was serving as a Chaplain at Bordeaux’s Foundling Hospital (Home for abandoned children). By this time, Fr. Guillaume de Védrines was a senior monk across town (Archives departementales de la Girande, Abbaye de Sainte-Croix, N. CCLXXIX, f.127, v.0, 3 November 1783). By the Spring of April 1788, he was bedridden in his cell (http://archives.cg33.fr/bibliotheque/docs/SERIE_H_00218745.pdf) and later died in August of that year. It’s highly likely that Fr. Barrière attended Fr. Guillaume de Védrines’ funeral in August 1788 at the Abbey of Sainte-Croix.

Another possible way that Fr. Barrière knew the Védrines Family is that he was from Bazas (the Cathedral where he was ordained). The Védrines Family home at the Chateau Doisy-Védrines near Barsac was in the Diocese of Bazas, only about 16 miles to the north of Bazas. In 1770, Pierre de Védrines (the older brother of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines) was still living at the Chateau Doisy-Védrines. Perhaps he knew the family then? Or in both ways?

Fr. Barrière retired once again when Fr. Rossi was assigned as the Pastor of Opelousas in 1818, but remained in residence there. Just as in St. Martinville after Fr. Isabey’s appointment, his name continues to appear for some months in the records of the parish in Opelousas, serving faithfully and quietly. And just as he had been before, he would be called to return once again to active duty.

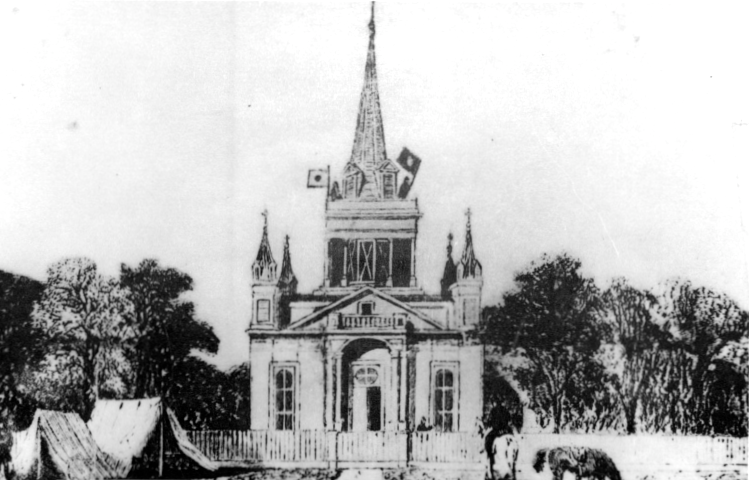

In May of 1822, Fr. Barrière was assigned as the first Pastor of the new parish of St. John at his old mission of Vermilionville (which is Lafayette today). He discussed his arrival in the note about the history of the parish, which is on the title page of the register of Baptisms and Funerals of the Black Catholics:

In May of 1822, Fr. Barrière was assigned as the first Pastor of the new parish of St. John at his old mission of Vermilionville (which is Lafayette today). He discussed his arrival in the note about the history of the parish, which is on the title page of the register of Baptisms and Funerals of the Black Catholics:

“The Priestly functions have been exercised regularly in this parish during, or about the month of June of this last year 1822. They were discharged by Father Brassac, rector of Grand Coteau, since about the time of the foundation of this church. Either the Pastor of the Attakapas, or myself, or the Pastor of Grand Coteau took care of this place before. Finally I was appointed resident Pastor of it about May of last year; and since then, have baptized in particular the following…”

Even though he arrived at Vermilionville in 1822, the register for black people didn’t begin until 1823, compiled from various notes he had made at the time he celebrated the sacraments. This delay in recording the entries was very different from what he had done in years before. Could this indicate that Fr. Barrière was now no longer the healthy and active missionary who used to spend days and weeks travelling on horseback from farm to farm across the prairies to exercise his Priestly ministry? The records at Vermilionville seem to indicate that they were written by an older man who was now weaker and more fragile.

For example, in one note he briefly mentions how sickness now slowed him down:

“I believe that these are all the Baptisms of slaves which I have performed, and also the burials at which I presided, during or since the month of June to December, all in 1822; but as at that time I fell very sick, it may well be that I forgot some of them, especially burials. For this reason I leave here these two lines blank, to write them thereon, in case I should discover any” (Rev Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.253).

He probably did forget some because there are no entries of burials performed by him even though there were many deaths during the fall of 1822, due to the epidemic of yellow fever, which brought so many difficulties throughout Louisiana that year.

He mentions his sickness again in another interesting entry of the burial of one of his own slaves: “Casimir, negro belonging to Mr. Barriere, Pastor of this parish of St. John, died and was buried in the cemetery of this parish, the second or third of the year 1823, during my great illness. He was the natural son of Marie Louise and Michel, my negroes. In witness whereof Barrière, pastor of St. John.”

After he recovered from his “great illness”, Fr. Barrière completed his pastoral duties quietly and humbly for about another year at Vermilionville. The active missionary life, which had been a great part of his Priestly service for so many years on the Louisiana Prairie, was now more difficult for him. As he approached the age of seventy, he surely yearned to see his native land once again.

The final funeral Fr. Barrière celebrated at Vermilionville was on March 1, 1824. And his last Baptism was a few days later on the fifth. Shortly after, he sold his animals, tools and two slaves, Francois, age fourteen and Bernard, age ten for $1,900 (Racines et Rameaux d’Acadie, Bulletin n. 17, Rev. Donald Hebert, Nov. 1997, p.4). Then he boarded the ship for his native land of Bordeaux after having lived and worked faithfully in Louisiana for thirty long years.

Several historians in America have erroneously asserted that Fr. Barrière died only eight days after returning to France (Rev. M.J. Spalding, Sketches of the Early Catholic Missions of Kentucky, Louisville: B.J. Webb and Brother, 1844, p.63; See also Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M., Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, St. Louis, MO: 1920, p.245 and Jim Bradshaw, Priest Fled French Revolution). In reality, however, it was eight years. He returned to his motherland twenty years after the Concordat was signed and religious peace had returned, but many of the churches were still without a resident Priest or Pastor. Fr. Michel Barrière offered his services to the Archbishop, who first thought that he should be given an important parish because of his background; but, at the same time, it couldn’t be one that would be too heavy of a burden for him since he was now sixty eight years old. At the edge of the Archdiocese of Bordeaux, the parish of Saucats was open. The Archbishop offered it to Fr. Barrière, but he refused it. But just as he had done so often in his missionary endeavors in Louisiana, he settled for a Parish in the forest, which had no Priest for more than a quarter century.

The Municipal Council of Cabanac had asked the Archbishop for several years for a resident Priest. Finally, they were given one. Fr. Barrière was appointed Curé on December 1, 1824.

His arrival was in many ways providential, and he was welcomed with great enthusiasm. Even though there was no longer a rectory since the last one had been taken over by the State and sold, the parishioners didn’t hesitate to raise the money to accommodate their new Pastor. A new rectory was built, with all the parishioners participating (See the history of the parish, http://www.si-graves-montesquieu.fr/9-eglises-romanes/328-les-2-eglises-de-cabanac-et-villagrains). Fr. Barrière found himself surrounded by the same spirit of the people he had served in Louisiana. He generously served the faithful at Cabanac-Villagrain until he died on October 2, 1832.

The stone plaque erected in his honor in the church of Cabanac proves how much his  parishioners loved their Pastor. Their words indicate that they knew about his suffering and fight for his faith during the Revolution and revered him for having devoted his life to those most in need: children abandoned at birth by their mother, the Acadians and Creoles both seeking their new homeland in Louisiana, and finally, his fellow citizens of France, whom the Revolution had abandoned in their forests without any spiritual aid.

parishioners loved their Pastor. Their words indicate that they knew about his suffering and fight for his faith during the Revolution and revered him for having devoted his life to those most in need: children abandoned at birth by their mother, the Acadians and Creoles both seeking their new homeland in Louisiana, and finally, his fellow citizens of France, whom the Revolution had abandoned in their forests without any spiritual aid.

Yes, Fr. Barrière lived an extraordinary life as a tremendous Priest. And yes, that life should be better known, particularly by those from the Vidrine Family who owe much to his loving service to their ancestors and their parish’s history. May he now enjoy true rest from his labors and receive the reward of eternal happiness promised to those who remained faithful even through persecution and the hardships of missionary life.