275th Anniversary: The Opelousas Post

The Vidrine Family in LA celebrates the 275th anniversary of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ departure from France and arrival of LA in 2018. It’s a great time to remember and reflect on the 275 years of history of his descendants and the life and family he established in LA.

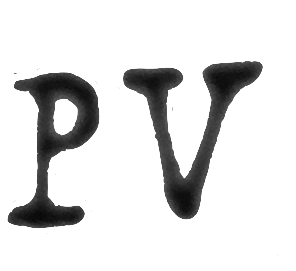

Even while still living at Pointe Coupée (1765-1773), it appears that Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines homesteaded some property at the Opelousas Post (near Washington, LA). Some speculate that he did so as early as 1769. If so, it was most likely used as a vacherie or farm similar to what his family in France had at Lapeze, outside of Ste-Livrade. We know that he registered a cattle brand in the Opelousas District in 1770.

de Védrines homesteaded some property at the Opelousas Post (near Washington, LA). Some speculate that he did so as early as 1769. If so, it was most likely used as a vacherie or farm similar to what his family in France had at Lapeze, outside of Ste-Livrade. We know that he registered a cattle brand in the Opelousas District in 1770.

However, by May 1773, Jean Baptiste received a grant of land at the Opelousas Post from the Spanish Government. (Pointe Coupee Documents, 1762-1803: A Calendar of Civil Records for the Province of Louisiana, Winston Deville, p. 100 (Apendix)). So eight years after arriving at Pointe Coupée, he departed, moving his family west to the Opelousas Post…leaving no trace of the Védrines family there (as at New Orleans) except for the information about them in the civil and ecclesiastical records. From then on, the base of the Védrines-Vidrine Family in LA would be in the Opelousas District.

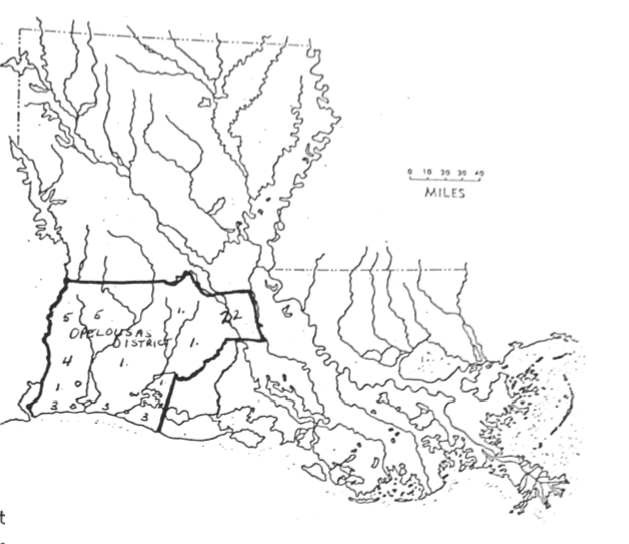

The area called Opelousas was very large in the middle of the 18th century when the Védrines-Vidrine family arrived. The Opelousas Post extended to the north all the way to the District of Natchitoches, with its dependent post of Rapides, northeast as far as the Avoyelles District, and east to Pointe Coupee. The boarder to the southwest was the Attakapas District, and to the south was the Gulf of Mexico. Indicating the area’s size, the early French settlers in the Opelousas territory called it simply “the west” during most of the 18th century.

The area called Opelousas was very large in the middle of the 18th century when the Védrines-Vidrine family arrived. The Opelousas Post extended to the north all the way to the District of Natchitoches, with its dependent post of Rapides, northeast as far as the Avoyelles District, and east to Pointe Coupee. The boarder to the southwest was the Attakapas District, and to the south was the Gulf of Mexico. Indicating the area’s size, the early French settlers in the Opelousas territory called it simply “the west” during most of the 18th century.

On a map dated 1716 drawn by a French missionary Priest, the name “Loupelousas” is found, most likely referring to the Native Americans who inhabited southwest Louisiana at the time (Henri Gravier, La Colonisation de la Louisiana a l”Epoque de Law, 1717-1721, Paris, Masson, 1904, p. 78).

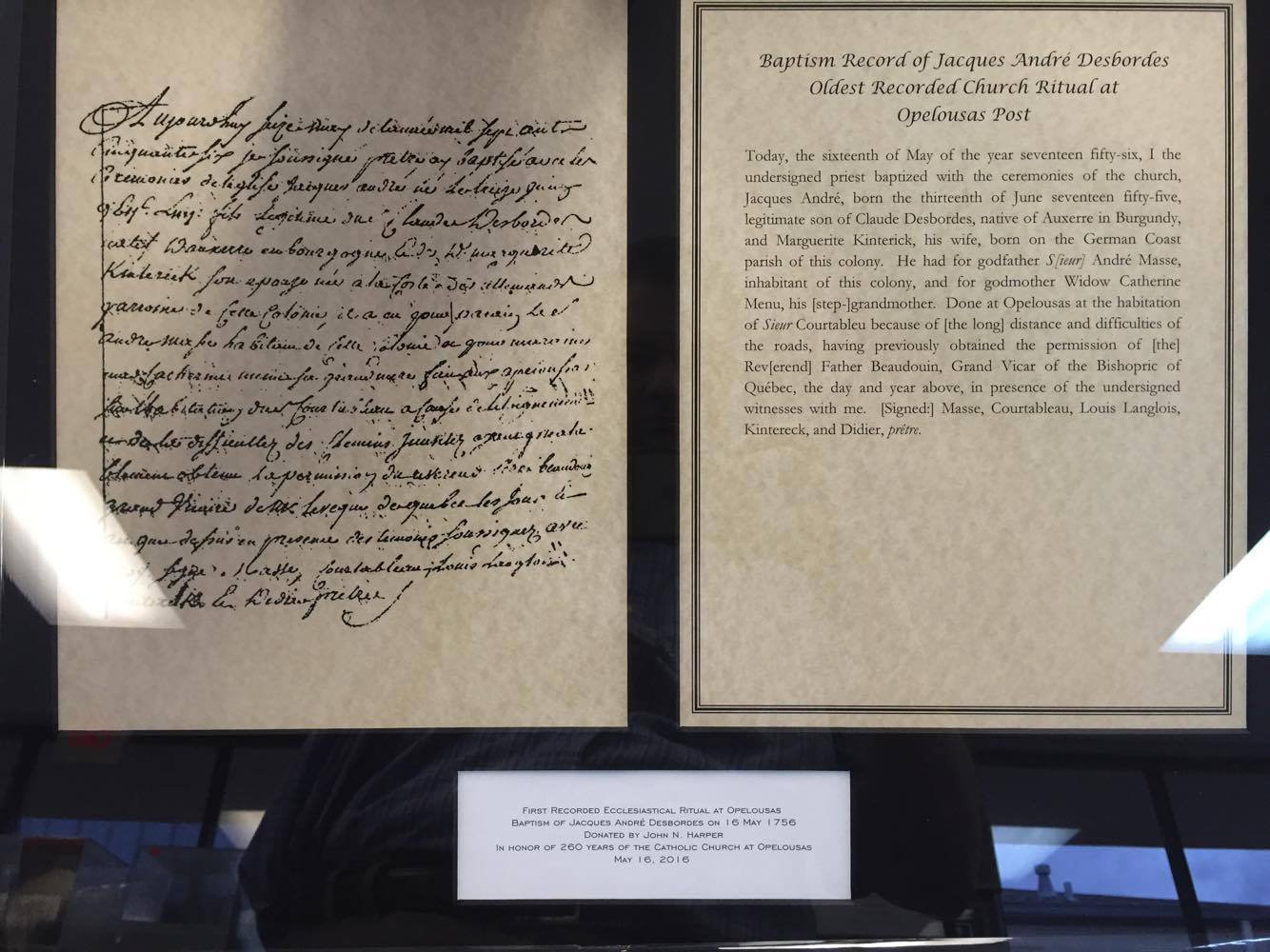

The first recorded sacrament at the Opelousas Post was a baptism on May 16, 1756 by Fr. Pierre Didier, OSB, a missionary Benedictine Priest who was covering the territory from  Natchitoches to Pointe Coupée. He baptized Jacques André Desbordes, the grandson of Joseph Le Kintrek, an early trader in the area. The note which Fr. Didier attached to the sacramental records at Pointe Coupée says: “(This act was) done at the house of Sieur Courtableau. Because of the distance and the difficulty of roads, (I) have obtained the permission of the Reverend Father Caudoin, Grand Vicar, and (the) Bishop of Quebec (to perform ecclesiastical rites there) today and following years.”

Natchitoches to Pointe Coupée. He baptized Jacques André Desbordes, the grandson of Joseph Le Kintrek, an early trader in the area. The note which Fr. Didier attached to the sacramental records at Pointe Coupée says: “(This act was) done at the house of Sieur Courtableau. Because of the distance and the difficulty of roads, (I) have obtained the permission of the Reverend Father Caudoin, Grand Vicar, and (the) Bishop of Quebec (to perform ecclesiastical rites there) today and following years.”

Starting then, the home of Jacques Courtableau was used by the inhabitants of the Opelousas Post for Holy Mass and the Sacraments by the missionary Priests until a church could be built.

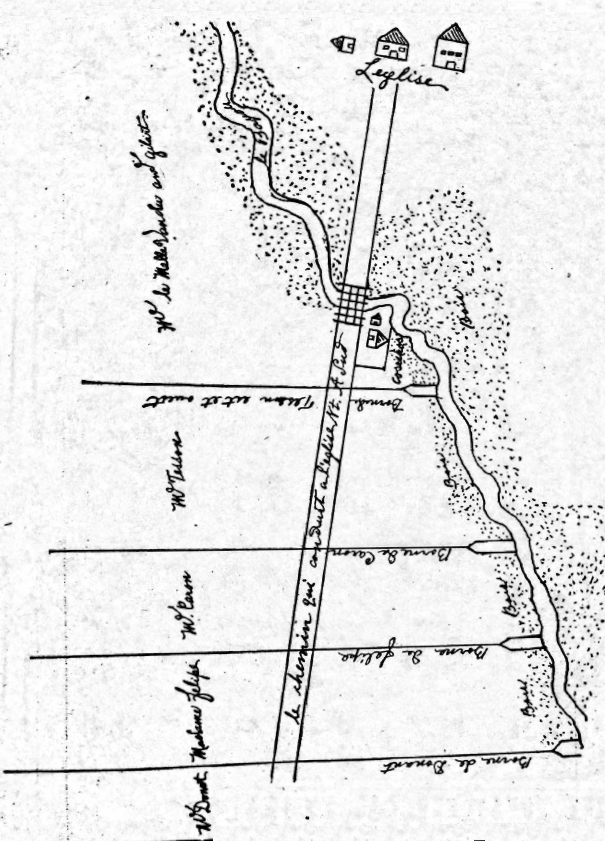

A small church at the Opelousas Post was finally built by parishioners in 1767. It was most likely similar to the one Fr. Baudier described: “a plain, simple little chapel, so small indeed that only a few people…could attend divine worship” (Roger Baudier, The Catholic Church in Louisiana, A.W. Hyatt stationery mfg. Company, Limited, New Orleans, 1939, pp. 238-39). The location was almost certainly on a tract of land between Bayou Carron and Bayou Courtableau in present day Washington, which was shown on a map of the church property drawn about twelve years later (see below).

According to the church parish’s oldest records, the church was officially founded in 1770 as La Iglesia Parroquial de la Immaculada Concepción del Puesto de Opeluzas (The Parish Church of the Immaculate Conception of the Post of Opelousas) by the French Capuchin friars. Early civil records make mention of ecclesiastical activity at “the parish church…” as early as 1766 (See History of St. Landry Church, stlandrycatholicchurch.org).

After receiving the grant of land at the Opelousas Post (present day Washington, LA) on May 10, 1773, Jean Baptiste and his family settled there, joining many other of his follow retired French Marines from Fort Toulouse, AL (Soileau, Guillory, LaFleur, Fontenot, Doucet, and Brignac, etc) and others from Pointe Coupee (Deshotel, Landreneau and Lemoine, etc) as well as a few Acadian families who were allowed to settle at the Opelousas Post (Pitre, Lejeune, Thibodeaux, etc), in addition to some Spanish, Italian, and Irish immigrants. Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines farmed cattle, as many others who settled in LA did, even giving up previous professions they had in France or other places to do so (David Lanclos, The letters of Dr. Franc̦ois Robin 1784-1826, 2009, p. 26).

Around the time that the Védrines-Vidrine family settled at the Opelousas Post, or shortly  after, a second church building was constructed in 1774, which was both larger and more ornamented than the original one. It’s this church that appears on a map drawn for a land dispute in 1780. By that time, the map shows a three-building complex (Cabildo, New Orleans). It seems to correlate with another document, dated September 7, 1780, which says that repairs were made on three church properties: the church house, the presbytery, and the kitchen. Jean Baptiste’s property was to the north west of the church.

after, a second church building was constructed in 1774, which was both larger and more ornamented than the original one. It’s this church that appears on a map drawn for a land dispute in 1780. By that time, the map shows a three-building complex (Cabildo, New Orleans). It seems to correlate with another document, dated September 7, 1780, which says that repairs were made on three church properties: the church house, the presbytery, and the kitchen. Jean Baptiste’s property was to the north west of the church.

Having retired from a life of service with the French Marines and settled at the property on which he would remain, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines was listed on the Opelousas Militia Roll on April 15, 1776. Of the 127 men listed, 34 were exempt from duty due to age or infirmity. [Jean Baptiste Lapaise] Pierre de Vidrine appears among the exempt. (Muster Roll of the Opelousas Militia, April 15, 1776, AGI, PPC, legajo 161) During the early days of the Louisiana Colony, it was the duty of all able young men to serve in the Militia, and to do their part to insure the protection of all. There’s no doubt Jean Baptiste was thankful that he was too old to serve as many of his neighbors left to join the Spanish in the fight against the English, his old foe.

Choosing to join in the American Revolution, King Charles III of Spain officially declared war against Britain on May 8, 1779. Two months later on July 8, 1779, he invited Spanish  subjects in North America to join. Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spanish Governor of Louisiana at that time, made immediate plans for a campaign to take the English colony of West Florida, which then extended all the way to the Mississippi River, for the King of Spain. By that fall, he was prepared and took the fight with his Louisiana soldiers to the British, forcing them to surrender. They agreed to surrender Natchez as well. Amazingly, throughout the series of events known as the Battle of Baton Rouge, only one person from Gálvez’s party died. A local justice of the peace joked that the British surrendered during the “mighty battle” because a British officer “wounded his head on his tea table.” (Chris Dier, Louisiana’s Fight in the Revolutionary War, https://yatlagniappe.com).

subjects in North America to join. Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spanish Governor of Louisiana at that time, made immediate plans for a campaign to take the English colony of West Florida, which then extended all the way to the Mississippi River, for the King of Spain. By that fall, he was prepared and took the fight with his Louisiana soldiers to the British, forcing them to surrender. They agreed to surrender Natchez as well. Amazingly, throughout the series of events known as the Battle of Baton Rouge, only one person from Gálvez’s party died. A local justice of the peace joked that the British surrendered during the “mighty battle” because a British officer “wounded his head on his tea table.” (Chris Dier, Louisiana’s Fight in the Revolutionary War, https://yatlagniappe.com).

While the Battle of Baton Rouge may not be well known in the larger scope of the Revolutionary War, the assistance Louisiana gave to Spain was vital to the War. And that was only possible because Gálvez received the support of early Louisiana residents, which included Acadians at the Attakapas Post, free people of color, Isleños from St. Bernard Parish, German immigrants along the German Coast, and French Creoles at the Opelousas Post. While it was the first time they all came together for the common cause of fighting against a foreign enemy, it would not be the last time they did so.

Later in the same year that Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines was listed as exempt in the Militia of the Opelousas Post, Elisabeth de Moncharvaux gave birth to their seventh and final child – their fifth girl – Eugenie Vidrine. She was born on September 22, 1776 at the Opelousas Post, LA and baptized on the same day at the church (St. Landry, V.1, p.8).

The Spanish Census of the Opelousas Post taken a few months later in May 1777, does not list Eugenie Vidrine. It is believed that like Marie Anne Vidrine in Pointe Coupee, Eugenie died sometime within the first few months after her birth. Listed in the Census of 1777 are Jean Baptiste and Elisabeth along with Pierre (age 15), Agnes (age 14), Perrine (age 12), and Etienne (age 7). Also listed are 7 cattle, 1 horse, and a negro slave named Cizar (age 32).

While a record of it has not yet been found, it is believed that the oldest child and first daughter of Jean Baptiste Lapaise and Elisabeth, Marie Jeanne Vidrine, was the first of their children to get married. She married Jean Baptiste Richaume Soileau at Immaculate Conception church of the Opelousas Post late in 1776 or early in 1777. The 1777 Census  seems to confirm this since she doesn’t appear in it with the Vidrine family.

seems to confirm this since she doesn’t appear in it with the Vidrine family.

Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines purchased another 20 arpents of land to the immediate north of the property he had at the Opelousas Post, LA on June 23, 1777, which was ratified on May 29, 1779 (Spanish Colonial Land Grant Papers, Folder 3, 23 June 1777).

The following year, on September 17, 1778, the second daughter and third child of Jean Baptiste and Elisabeth de Védrines, Agnes Vidrine married Saut Joseph Rosa (Rozas) at the church at the Opelousas Post (LSAR Opel. 1787). He came to LA from Québec.

Dr. Francois Robin, an immigrant from France who was Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ brother in law (married to Elisabeth de Moncharvaux’s sister, Marie Anne de Moncharvaux) gives us a glimpse of life on the Opelousas Prairie in 1784:

“In Opelousas, the people there do not eat bread. They live only on rice and Spanish wheat, which are the only grains that grow there, as well as in New Orleans. But fish and game are extremely abundant. That, my dear parents, is a picture of this country, where the water is the same height as the land. All the houses are constructed of wood, having no stone available” (David Lanclos, The letters of Dr. Franc̦ois Robin 1784-1826, 2009, p. 9).

A year after Dr. Robin’s letter, another Spanish Census was taken in April 1785 by Commandant Alexandre DeClouet. Jean Baptiste and Elisabeth are listed along with Pierre (age 23) and Perrine (19) – both still at home! – as well as their younger brother Etienne (age 14). 1 male slave and 1 female slave are also listed, both over 50.

A year after Dr. Robin’s letter, another Spanish Census was taken in April 1785 by Commandant Alexandre DeClouet. Jean Baptiste and Elisabeth are listed along with Pierre (age 23) and Perrine (19) – both still at home! – as well as their younger brother Etienne (age 14). 1 male slave and 1 female slave are also listed, both over 50.

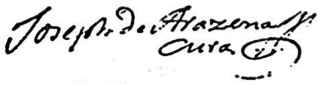

A few months later, on July 24, 1785, Fr. Joseph de Arazena, O.F.M.Cap. arrived as the Pastor of the church at the Opelousas Post. He found that it was once again necessary to repair the presbytery and improve the church property (Winston Deville, Opelousas: The History of a French and Spanish Military Post in America, 1716-1803, Cottonport, LA, Polyanthos, 1973).

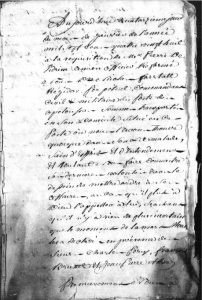

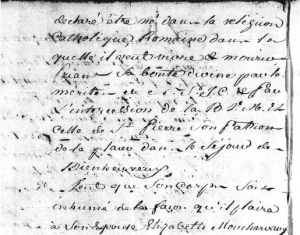

About 25 years after arriving and settling at the Opelousas Post, Jean Baptiste Lapaise died there. From the Sacramental records, we know that he had a blessed death. The Spanish Pastor of the Opelousas Post, Fr. Joseph de Arezema wrote that the day before he died, he visited the home of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines and that: “Jean de Vedrine…received the Sacraments of Penance, Euchariste, & Extreme Unction “con particular devocion” (with particular devotion or piety)”(St Landry, V. 1-A, p. 5).

The Civil Records corroborate the Sacramental records. On that same day, Monday, January 14, 1788, the Commandant of the Opelousas Post and several witnesses went to his home where he expressed and signed his will. He beautifully expressed his deep awareness of his human frailty in the face of the mystery of death and his hope of Eternal Life in Christ the day before he died! What a precious heritage he has left the Vidrine Family!

The Civil Records corroborate the Sacramental records. On that same day, Monday, January 14, 1788, the Commandant of the Opelousas Post and several witnesses went to his home where he expressed and signed his will. He beautifully expressed his deep awareness of his human frailty in the face of the mystery of death and his hope of Eternal Life in Christ the day before he died! What a precious heritage he has left the Vidrine Family!

“Today, the fourteenth day of the month of January in the year one thousand seven hundred eighty eight at the request of Mr. Pierre De Vidrine, retired former Officer, I, Mr. Nicolas Forstall, Perpetual Director of the Superior Court and Civil and Military Commandant of the Post of Opelousas was summoned and transported to his domicile situated in this Post where we have found the above mentioned in his bed sick, with sound mind and judgment, and making known his last wish, bothering to put his affairs in order so that he may be pleasing to God who will call him, knowing that there is nothing more uncertain than the moment of death – has declared to us in the presence of Mrs. Charles Perry, Francis Brunet and Jean Pierre Moreau:

– Firstly, he declared to us that he was born in the Roman Catholic religion, in which he  would like to live and die rich in God’s grace by the merits of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary and that of St. Peter, his Patron whom he has been placed under during his blessed journey.

would like to live and die rich in God’s grace by the merits of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary and that of St. Peter, his Patron whom he has been placed under during his blessed journey.

– Wants that his body be buried in the manner that he has discussed with his spouse, Elisabeth Moncharvaux…”

From the same records, we know that he died the next day, on Tuesday, January 15, 1788. The wake was held for him at his home and Holy Mass was offered for him the next day, on Wednesday, January 16, 1788, at the church of the Immaculate Conception at the Opelousas Post (Washington, LA) by Fr. Arezema. Afterward, he was buried in the cemetery of the Opelousas Post (St Landry, V. 1-A, p. 5). Sadly, his tomb can no long be found.

Some soldiers deserted the French Marines along the way during the Colonial period, while most of the Marines served honorably and remained faithful to their commitments, choosing afterward to either stay in the colony of Louisiana or to return to France to be discharged or reassigned elsewhere. Of the soldiers who decided to remain in Louisiana, the most interesting, especially to genealogists, are the ones who established families in LA, leaving behind traces of their lives in the surviving colonial records. This is the case with Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines. All of the sacramental and civil colonial records – in both France and Louisiana – bear witness that he served the French Marines honorably, and having established a family in Louisiana, settled there to live and die, the first of the Védrines family in France to do so.

Some soldiers deserted the French Marines along the way during the Colonial period, while most of the Marines served honorably and remained faithful to their commitments, choosing afterward to either stay in the colony of Louisiana or to return to France to be discharged or reassigned elsewhere. Of the soldiers who decided to remain in Louisiana, the most interesting, especially to genealogists, are the ones who established families in LA, leaving behind traces of their lives in the surviving colonial records. This is the case with Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines. All of the sacramental and civil colonial records – in both France and Louisiana – bear witness that he served the French Marines honorably, and having established a family in Louisiana, settled there to live and die, the first of the Védrines family in France to do so.

While still grieving for her husband and their father, the summer of 1788 must have been an exciting one for Elisabeth and the rest of the Védrines-Vidrine family. About five months after his father’s death, the oldest son, Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine was married to  Marie-Josephe Brignac on July 7, 1788 at the church of the Opelousas Post (Washington, LA) by Fr. Joseph de Arazena (St. Landry, V.1-A, p.16). One week later, Fr. Joseph de Arazena was busy again with the Vidrine family as the second daughter, Perrine Vidrine married Charles dit Belaire Fontenot on July 12, 1788 (St. Landry, V.1, p.17).

Marie-Josephe Brignac on July 7, 1788 at the church of the Opelousas Post (Washington, LA) by Fr. Joseph de Arazena (St. Landry, V.1-A, p.16). One week later, Fr. Joseph de Arazena was busy again with the Vidrine family as the second daughter, Perrine Vidrine married Charles dit Belaire Fontenot on July 12, 1788 (St. Landry, V.1, p.17).

Since Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine and Perrine both married after their father passed away, neither of them had children before he died. However, it seems that he had been able to know three of his Fontenot grandchildren whom Marie Jeanne gave birth to (in 1776, 1777, and 1778).

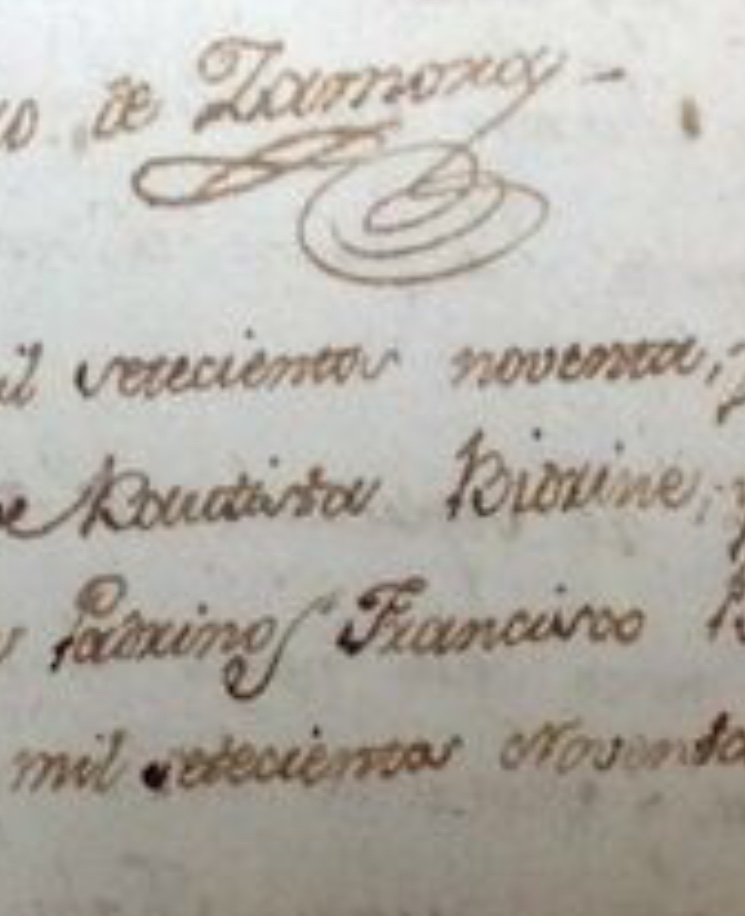

The first-born son of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine and Marie-Josephe Brignac, Pierre Vidrine, Jr. was born on January 3, 1790 and baptized a month afterward (V.1-A, p.96). Their second son, Lisandre Jean Baptiste Vidrine was born on August 29, 1791 and baptized a month later (V.1, p.113). They then had two daughters, Marie Celestine Vidrine born on April 14, 1793 and Hyacinth Vidrine born a year later.

In 1792, the name of the church at the Opelousas Post was changed from Immaculate Conception to St. Landry.

Jean Baptiste Lapaise and Elisabeth’s second son, Etienne Vidrine dit Lapaise was married  to Victoire Soileau on August 19, 1795 at the church at the Opelousas Post (V.1, p.57) by Fr. Pedro de Zamora, O.F.M.Cap., another Spanish Capuchin who took control of the parish in 1789. He wrote “Bidrine” instead of Vidrine, apparently hearing the name with a B. Fr. Barriere would later go back and make notations on Fr. Zamora’s entries, correcting the spelling to V instead of B for the Vidrine Family.

to Victoire Soileau on August 19, 1795 at the church at the Opelousas Post (V.1, p.57) by Fr. Pedro de Zamora, O.F.M.Cap., another Spanish Capuchin who took control of the parish in 1789. He wrote “Bidrine” instead of Vidrine, apparently hearing the name with a B. Fr. Barriere would later go back and make notations on Fr. Zamora’s entries, correcting the spelling to V instead of B for the Vidrine Family.

The Spanish Census of the Opelousas Post taken the following year, on May 23, 1796, lists Elisabeth de Moncharvaux as a widow living in the “Quartier de L’Eglise” the area around the church (Washington, LA). By then, other Quartiers or districts had sprung up with movement around the Opelousas Post.

Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine is also listed in the Census of 1796 at the Quartier de L’Eglise near his mother. However, he appears to have also homesteaded land to the west in the Prairie known as the Quartier dit Baton Rouge (which would later be named Ville Platte) some time before 1796, while retaining his land at the Opelousas Post (Washington, LA). His brother Etienne Vidrine followed after him, settling on land in September of 1796 next to his brother at the Quartier dit Baton Rouge, which he bought from his father in law, Noel Soileau. Etienne and Victoire’s first born, Etienne Vidrine, Jr. was born on February 12, 1797. That same year on Christmas day, Jean Baptiste Pierre and Marie-Joseph’s fifth child and third son, Florentin Pierre Vidrine Sr., was born.

Around this time, Fr. Pedro de Zamora requested permission to move the church at the Opelousas Post from its original location near Bayou Courtableau to the center of the post’s population (where it currently is located). Permission was granted and in 1796, land for the new church about five miles to the south was donated by Michel Prudhomme, a wealthy planter and cattle farmer, along with Madame Tesson. Instead of moving the former church, it was decided that a new one would be built. With cypress furnished partly by Prudhomme, the church, presbytère and other buildings that made up the church complex were built and completed on June 17, 1798. (History of St. Landry Church, stlandrycatholicchurch.org).

The church being renamed and moved from its original location at the Opelousas Post was probably a major adjustment for the people who had lived near it and whose lives literally revolved around it. However, a much larger change was coming, which would affect not only the people of the Opelousas Post, but the whole of the Colonial Louisiana Territory.

The Louisiana Purchase Treaty, in which Napoleon ceded the Louisiana Territory to the United States was signed in Paris on April 30, 1803. According to Article III, the “…inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be incorporated into the Union of the United States and admitted as soon as possible according to the principles of the federal constitution.” It took several years for it to happen, but on April 30, 1812, Louisiana finally entered the Union as the 18th state.

A few months after the LA Purchase, on October of 1803, Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine sold his land at the Opelousas Post and filed a land claim at the Quartier dit Baton Rouge (which was later named Ville Platte) in February of 1806 for the land he had previously homesteaded under the Spanish government. Also in 1803, Etienne sold the property he had purchased next to his brother, Jean Baptiste Pierre and moved to the south west of his former property, filing a land claim in June of 1807.

At this time – in the middle of the transition of the LA territory from Spain to the United States – Dr. Francois Robin observed:

“This country here, which a few years previously

contained only savages, is inhabited with an infinite number of Frenchmen who are obliged to submit themselves to occupations of every kind in order to survive. This country is abounding in preceptors, teachers of dance, pack merchants, merchants of this and that. This country, which is rich due to its productivity, has just been ceded to the Americans. What will become of us in this new regime; these new morals and idioms, this religion, and all of the superiority that characterizes this Anglican nation? The only thing I can say is that Spain suffices for us” (David Lanclos, The letters of Dr. Franc̦ois Robin 1784-1826, 2009, p. 17).

We can imagine his sister-in-law, Elisbeth de Moncharvaux and her children had similar thoughts of what would come.

On November 20, 1806, Jean Gradnego’s land was sold which was next to “Dame Veuve de Vidrines”, indicating that Elisabeth was still living on their land at the Opelousas Post.

The move of both sons from the Quartier de l’Eglise at the Opelousas Post (which would later be Washington) where Jean Baptiste Lepaise and Elisabeth de Védrines had settled to the west at the Quartier dit Baton Rouge (which would later be Ville Platte) established that area as the new base of the Vidrine Family and their children.