275th Anniversary: Fort de Chartres

The Vidrine Family in LA celebrates the 275th anniversary of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ departure from France and arrival of LA in 2018. It’s a great time to remember and reflect on the details of the life he lived and the family he established after arriving.

Just as Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines had arrived in New Orleans with the new Administration of Governor Vaudreuil, he was appointed in May 1751 to serve at Fort Chartres in IL with the new Administration of Commandant Jean Jacques MaCarty Mactigue. The exact date of his arrival in the Pays des Illinois is unknown at this time. However, the first appearance of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines in the records of Kaskaskia is on July 22, 1751 (Kaskaskia Manuscripts 51:7:22:1), so he most likely departed New Orleans the spring of 1751 in the special convoy that headed up the Mississippi that year (AN Col. C13 A34 f. 277), or he could have made the trip in an earlier convoy. Chevalier Jean Jacques MaCarty Mactigue departed New Orleans in the fall convoy and arrived as the commandant of Fort Chartres later that year in December of 1751. They both arrived in the Pays des Illinois and would serve there during exciting and challenging times, particularly as a new stone Fort would be constructed and the French and Indian War (also called the Seven Years War) would break out.

However, the first appearance of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines in the records of Kaskaskia is on July 22, 1751 (Kaskaskia Manuscripts 51:7:22:1), so he most likely departed New Orleans the spring of 1751 in the special convoy that headed up the Mississippi that year (AN Col. C13 A34 f. 277), or he could have made the trip in an earlier convoy. Chevalier Jean Jacques MaCarty Mactigue departed New Orleans in the fall convoy and arrived as the commandant of Fort Chartres later that year in December of 1751. They both arrived in the Pays des Illinois and would serve there during exciting and challenging times, particularly as a new stone Fort would be constructed and the French and Indian War (also called the Seven Years War) would break out.

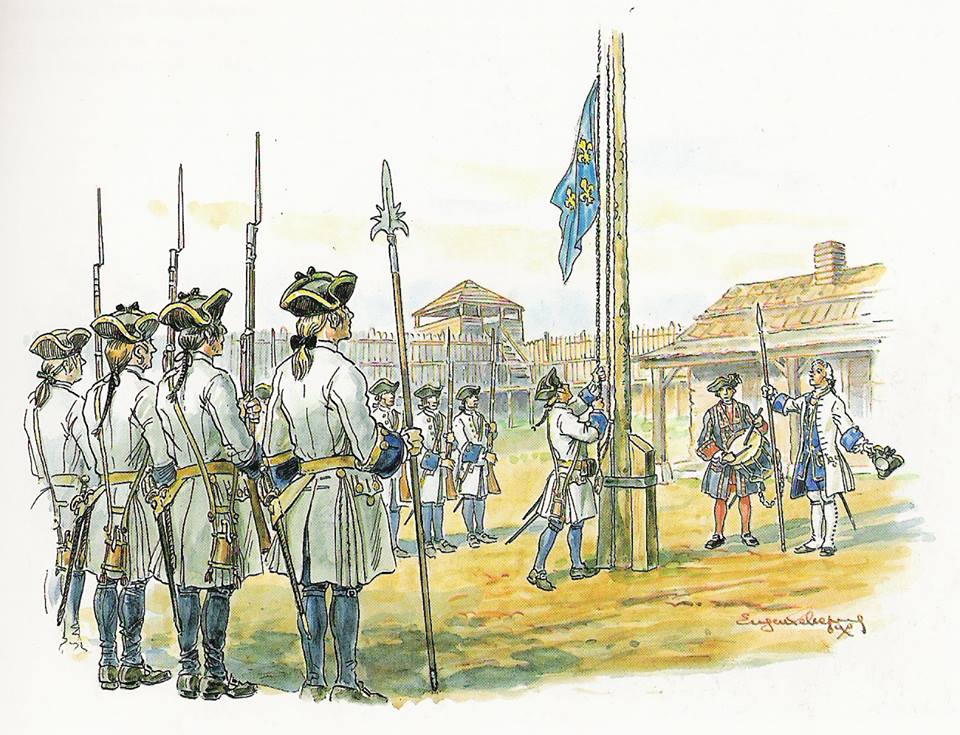

At the same time that the city of New Orleans was being founded in the Lower Louisiana Territory, the French were working to establish a presence in Upper Louisiana, which would later be known as the Pays des Illinois. In 1719, the French established the first Fort de Chartres on the east bank of the Mississippi River about 16 miles north of the village of Kaskaskia. Around the Fort, a village began to grow up known simply as Chartres or Nouvelle Chartres.

However, five years after the original Fort was built, flooding from the Mississippi River and the weather conditions of the area in general had left it in bad condition. Construction of a second wooden Fort began in 1725, this time, further from the river, but still on the flood plain. It took a little longer for the second wooden Fort to deteriorate, but a third wooden Fort had to be constructed in 1732. Within ten years, by 1742, the third wooden Fort too was merely a rotting little stockade, its equipment dissipated. By 1747, “the commandant moved most of the soldiers to Kaskaskia…Only a small detachment remained at the Fort.” (David MacDonald, Lives of Fort de Chartres: Commandants, Soldiers, and Civilians in French Illinois, 1720–1770, Shawnee Books, 2016, p. 24).

This is how commandant Jean Jacques MaCarty Mactigue found the condition of the Fort when he arrived:

“Late in 1751, Macarty, the newly appointed commandant, noted that while the frames of the buildings within the fort were good, the buildings needed other significant repairs and one was close to collapse.” (David MacDonald, Lives of Fort de Chartres, Shawnee Books, 2016, p. 24).

He was given orders to build a new Fort of stone.

While we currently know very little about his eight years of service in New Orleans as an Officer of the French Marines, we are able to know more about Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ years in the Pays des Illinois serving at the Fort de Chartres. His name appears as a witness in several different civil records, as it also appears in the sacramental records. For example, at a Baptism on February 4, 1752, he served as the parrain or godfather of “a negro child, natural son of Margrite, a negress belonging to Flibot, habitant in this parish” (Baptismal record from St. Anne de Fort Chartres, now at St. Joseph in Prairie du Rocher, IL (Brown and Dean, The Village of Chartres in Colonial Illinois: 1720-1765, Polyanthos Press, 1977, p. 185, D-260). Filibot (or Philibot) was a relative of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ future wife, Elisabeth de Moncharvaux. The child was named Jean Baptiste, apparently after his parrain.

Later that year, on October 5, 1752, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines, was promoted to Enseigne en Second (AN Col., D2, C59, f.32).

Work on the new Fort designed by François Saucier was begun in 1753. A huge  structure of stone, plastered over, it covered four acres of ground and could accommodate 300-400 men. When completed, it was known as the strongest and most pretentious fortress in the new world. Years later, once the French lost the War to the British, Philip Pittman, writing in 1764, said: “It is generally allowed that this is the most commodious and best built fort in North America” (David MacDonald, Lives of Fort de Chartres, Shawnee Books, 2016, p. 25).

structure of stone, plastered over, it covered four acres of ground and could accommodate 300-400 men. When completed, it was known as the strongest and most pretentious fortress in the new world. Years later, once the French lost the War to the British, Philip Pittman, writing in 1764, said: “It is generally allowed that this is the most commodious and best built fort in North America” (David MacDonald, Lives of Fort de Chartres, Shawnee Books, 2016, p. 25).

That fall, from September to November 1753, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines was listed as an Enseigne in a Detachment of troops under Francois de Mazellieres at IL during a dangerous mission. According to a letter Macarty, commandant of Fort Chartres wrote to Governor Kerlérec in New Orleans, “a strong detachment which was composed of one hundred troops” under the command of Captain Mazellières, with Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines as one of the Officers (Enseigne en second) was given the mission to “provide a supply of provisions of all sorts for the subsistence of a detachment of three thousand men which was to leave Canada in the Spring of 1753 to come and fortify itself on the Ohio, Wabash, and Great Miami rivers”. Mazellières and his company left on September 1. However, as they advanced, they did not find the detachment from Canada:

“Not having found him he acted as follows: Having entered the Wabash and gained the entrance to the Ohio River he ascended it for about ninety leagues without being able to ascend it higher for want of water, and being stopped by a cascade or fall of about fifteen feet he took the decision of sending by land the Sieur Portneuf and some soldiers with orders to follow the river to discover the said army if it were possible. The Sieur Portneuf lost himself for three or four days in the depths of the forest through the ignorance of his guide, but having reached the river again he marched three days more, which brought him to the Shawnee village, where he saw several English traders and several of our soldiers who have deserted, some of whom have taken wives. On the eve of his arrival at the said village two Delaware Indians, or Mohawk, arrived who gave the Shawnee an account of the position of the detachment from Canada. They told them also that a party was established and entrenched at Presqu’Isle on Lake Erie, another at the river aux Boeufs, and that the remainder, commanded by the Sieur Péan, had returned to Canada. The Shawnee not having attacked the French save when they were found in parties of their enemies, the chief and some of the important men of the village told the Sieur de Portneuf that they would advise him to leave immediately, adding to him that their young men began to lose their understanding and wished to kill him, which obliged the Sieur de Portneuf to leave that same night. The Sieur des Mazellières, to whom but two months’ provisions had been given following the orders of M. Duquesne, not hearing any news of the Sieur de Portneuf nor of the army and having lost ten men by desertion and being threatened with not being able to keep one, took the decision of making an enclosure of upright pickets for a cache of all the provisions which he covered with canvas; after which he returned to the Illinois, where he arrived the nineteenth of November last and the Sieur Portneuf some days afterward” (AN Col. C13 A38, f.79; Pease, Theodore Calvin, Illinois on the Eve, 1940, pp. 861-868).

It appears that Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines returned safely to Fort Chartres with Captain Mazellières.

By the next year, in 1754, “Fort de Chartres mustered 285, probably the largest number in the history of the fort.” (David MacDonald, Lives of Fort de Chartres, Shawnee Books, p. 23). This was a description of the life at Fort Chartres under Commandant MaCarty given in 1921:

“The people of the fort and village led a merry life. Lordly processions of gentlemen and richly dressed ladies marched into the chapel to hear Mass. Hunting parties issued from the gates of the fort and returned at night full laden with spoils of the chase. Stately receptions were given, where officers in uniforms covered with gold lace danced with ladies robed in velvets and satins. The fashions of Paris were reproduced in this military station on the distant Mississippi. The fame of Fort Chartres spread to every settlement in the new world. It became a common saying, “All roads lead to Fort Chartres”” (Irwin F. Mather, The Making of Illinois, 1921, p. 87).

Around the same time, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ fellow French Marines were engaged in an interesting battle. England and France were still relatively at peace. But in May of 1754, Joseph Coulon de Villiers de Jumonville led a small detachment of French to notify the British that they were trespassing on territory claimed by France in the Ohio Country, including the territory of the upper Ohio River in what is today western Pennsylvania.

George Washington, a young British Officer commanding a detachment of Virginia militia, ambushed Jumonville’s party, killing him and several others. This event was one of the first battles of the Seven Years’ War. Jumonville’s brother Louis Coulon de Villiers later defeated Washington and forced his surrender at Fort Necessity…the only military surrender of his long career…and it happened on the 4th of July (1754)!

This is the description of that surrender:

“By 11:00am on the 3rd of July 1754, Louis Coulon de Villiers came within sight of Fort Necessity. Washington was occupying the Fort and began to prepare his garrison for an attack.

Coulon moved his troops into the woods, within easy musket range of the fort. Deciding to strike first, Washington ordered an assault with his entire force across the open field. Seeing the assault coming, Coulon ordered his soldiers, led by Indians, to charge directly at Washington’s line. However, the Virginians fled back to the fort, leaving Washington and the British greatly outnumbered. Washington ordered a retreat back to the fort.

Louis Coulon de Villiers sent an officer under a white flag to negotiate. Washington sent one of his officers along with a translator, to negotiate. As negotiations began, the Virginians, against Washington’s orders, broke into the fort’s liquor supply and got drunk. Coulon told the translator that all he wanted was that Washington surrender the garrison, and the Virginians could go back to Virginia. He warned, however, that if they did not surrender now, the Indians might storm the fort and scalp the entire garrison.

This message was brought to Washington, and he agreed to these basic terms. One of

Louis Coulon de Villiers’ aides wrote the terms of surrender and then gave them to Washington’s translator, who translated them for Washington because he couldn’t read French. Washington signed the document of surrender. On July 4, Washington and his troops abandoned Fort Necessity. And he and his troops headed back to eastern Virginia” (see Edward Lengel, General George Washington. New York: Random House, 2005, pp. 40-44).

So while Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines himself was not personally engaged in the battle against George Washington and his militia in 1754, it’s easy to imagine the joy Louis Coulon de Villers and his men shared with their fellow Marines when they arrived back at the Fort de Chartres, IL. Surely, at this point, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines never imagined that his sons would one day be living in a nation which would have George Washington as its first President! But now that it had begun, it was the Seven Years’ War that Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines and his fellow Marines would be engaged in during the rest of his time at the Fort de Chartres until they lost it to the British in 1763.

In 1757, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines is listed as an Enseigne en second in a detachment of troops under Louis Marie de Populus, Escuyer de St. Protais, at Cahokia, IL.

The next fall, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines was back at Fort Chartres making preparations to marry his Captain, Jean Baptiste François Tisserand De Moncharvaux’s daughter, Elisabeth de Moncharvaux. They married on October 10, 1758, at the chapel of Sainte Anne de Fort Chartres. Through her mother, she was the great granddaughter of Marie Rouensa, a full-blooded woman of the Kaskaskia Tribe of Native Americans. The Kaskaskia Tribe had arrived at the mouth of the Kaskaskia River where it met the Mississippi River around 1703. Marie Rouensa’s father, Chief Francois Xavier Mamentouensa Rouensa (1650-1725), was Chief of the Illini Confederation.

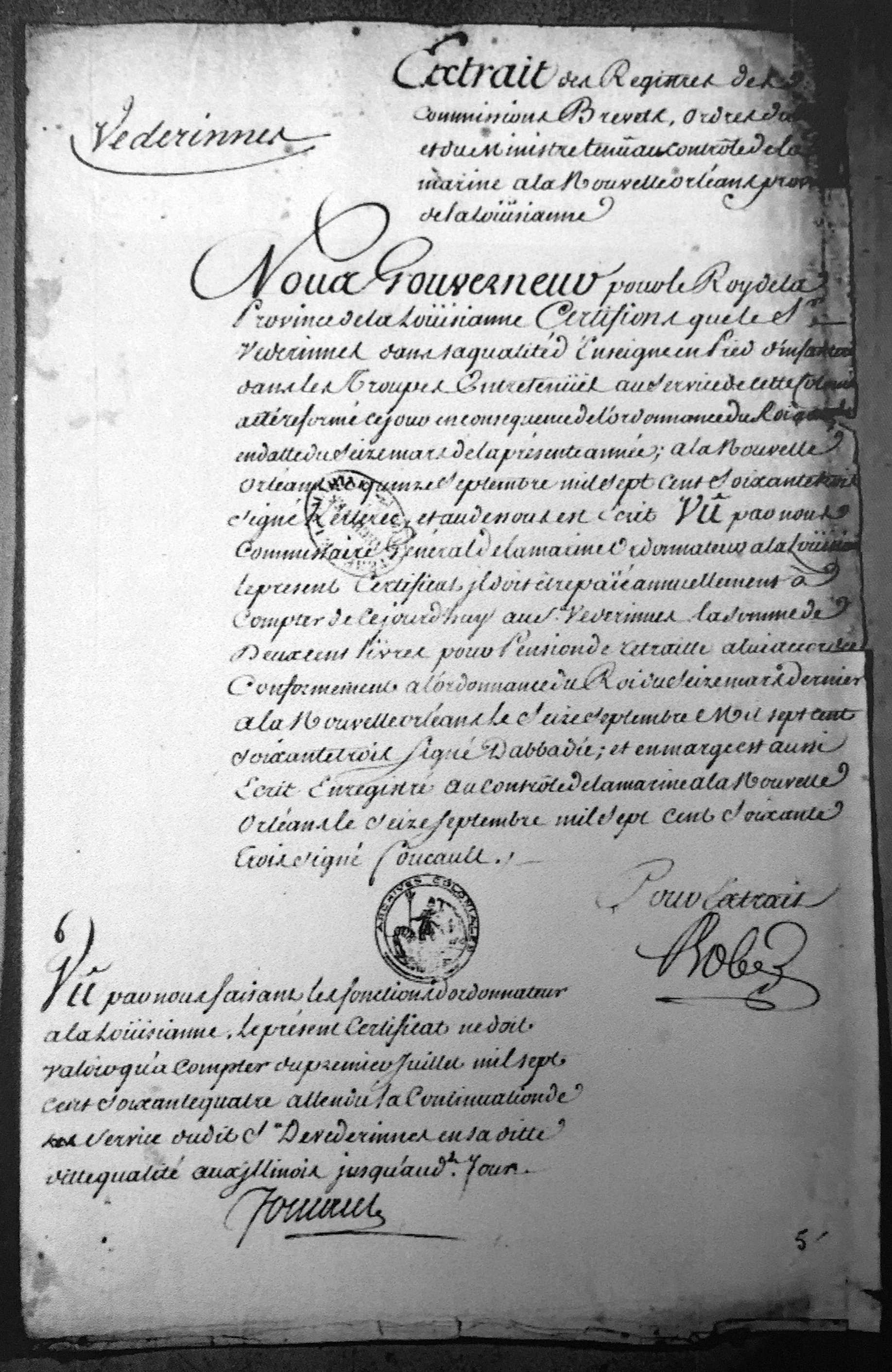

By the following year, in July of 1759, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines was promoted to Enseigne en Pied (AN Col., D2, C59, f.32).

Ensign De Védrines and his wife bought a lot in the town of New Chartres next to the Fort [one lot of twenty-five toises in front and thirty in depth, on which there is one shed built of pickets with a double stone chimney bounded in front by a great street of New Chartres] on November 17, 1760 (Kaskaskia Manuscripts 60:11:17:1), intending – it appears – to settle there. Two years later, around 1762, they had their first child and oldest son, Jean Baptiste Pierre de Védrines.

Ensign De Védrines and his wife bought a lot in the town of New Chartres next to the Fort [one lot of twenty-five toises in front and thirty in depth, on which there is one shed built of pickets with a double stone chimney bounded in front by a great street of New Chartres] on November 17, 1760 (Kaskaskia Manuscripts 60:11:17:1), intending – it appears – to settle there. Two years later, around 1762, they had their first child and oldest son, Jean Baptiste Pierre de Védrines.

However, the English defeated the French and in September of 1763, the Treaty of Paris was signed, granting all land east of the Mississippi (which included the Pays des Illinois) to England. A large number of the French inhabitants were unwilling to dwell in a land ruled by men of a different tongue and creed, whom they had been in conflict with for years. They sold their possessions and left the Illinois Country, many of them going to St. Genevieve or St. Louis on the other side of the Mississippi River. Others went south toward Natchez or New Orleans, which was now under the rule of the Spanish, and friendlier territory for those who were Catholic and spoke French like Jean Baptiste and his family. It appears that the Védrines had their second child and first daughter, Agnes Vidrine, in 1763, either as they prepared to leave the Illinois Country for New Orleans, or on the way there.

An ordinance was signed by King Louis XV on March 16, 1763, stipulating Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ retirement from the French Marines and the retirement pension he was to receive of 200 livres per year. They must have begun their descent down the Mississipi River some time after May 10 (Kaskaskia Manuscripts 63:5:10:1) in the summer of 1763 because Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ retirement was signed and dated in New Orleans on September 15, 1763 (AN D2 C59, f32). Commandant MaCarty had retired three years earlier and settled on his plantation near New Orleans (which later became the town, and then suburb of Carrollton). Perhaps the presence of the commandant he had served under nearly his whole time at Fort Chartres as well as many other soldiers from Fort Chartres he had served with had an influence, in part, on Jean Baptiste’s choice to go back to the city he had first arrived at from France, and which he had served for nine years before being sent up to the Illinois Country.

Lapaise de Védrines’ retirement from the French Marines and the retirement pension he was to receive of 200 livres per year. They must have begun their descent down the Mississipi River some time after May 10 (Kaskaskia Manuscripts 63:5:10:1) in the summer of 1763 because Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ retirement was signed and dated in New Orleans on September 15, 1763 (AN D2 C59, f32). Commandant MaCarty had retired three years earlier and settled on his plantation near New Orleans (which later became the town, and then suburb of Carrollton). Perhaps the presence of the commandant he had served under nearly his whole time at Fort Chartres as well as many other soldiers from Fort Chartres he had served with had an influence, in part, on Jean Baptiste’s choice to go back to the city he had first arrived at from France, and which he had served for nine years before being sent up to the Illinois Country.