275th Anniversary: Family of Elisabeth de Moncharvaux

The Vidrine Family in LA celebrates the 275th anniversary of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ departure from France and arrival of LA in 2018. It’s a great time to remember and reflect on the 275 years of history of his descendants and the family he established in LA.

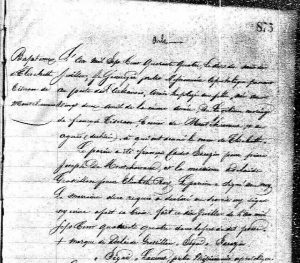

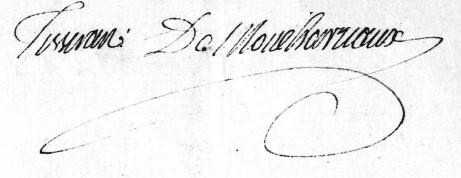

After arriving in LA in May of 1743 as an Officer in the French Marines (Cadet de l’aiguillette) and serving under Governor Vaudreuil in New Orleans for eight years, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines was in the Pays des Illinois by July 1751, where he was promoted to Enseigne en second the following year. Seven years after serving at Fort Chartres, in the fall of 1758, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines was making preparations to marry his Captain, Jean Baptiste François Tisserand De Moncharvaux’s daughter, Elisabeth de Moncharvaux. As an Officer, he had to get permission from Commandant Macarty (HMLO 325), which he apparently did because Macarty was also one of the witnesses of his marriage, which took place on October 10, 1758, at the chapel of Sainte Anne de Fort Chartres. Because Elisabeth de Moncharvaux carried her father’s French name, her maternal heritage is not immediately recognizable. However, her maternal ancestry most likely stretched back in the New World for centuries. Her maternal great grandmother was Marie Rouensa “Aramepinchone” (1677-1725), a full-blooded Native American of the Illinois Kaskaskia Tribe. So, whereas Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines arrived in LA from France, the young woman he married 15 years afterward was, in many ways, a native of the New World.

Elisabeth was born on April 22, 1744 at the Arkansas Fort along the Mississippi River at the mouth of the Arkansas River during the time her father, Jean Baptiste François Tisserand De Moncharvaux was serving as Commandant of the Fort (from 1739-1748) and baptized there on July 10. She moved to Fort Chartres, IL when her father was reassigned there, and was about 7 years old when Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines arrived in the Pays des Illinois.

the mouth of the Arkansas River during the time her father, Jean Baptiste François Tisserand De Moncharvaux was serving as Commandant of the Fort (from 1739-1748) and baptized there on July 10. She moved to Fort Chartres, IL when her father was reassigned there, and was about 7 years old when Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines arrived in the Pays des Illinois.

In LA, Elisabeth de Moncharvaux is often called an “Indian Princess” among Vidrine descendants when, in actual fact, she wasn’t quite so. It is true that she was part Native American. The Princess part probably comes from the fact that she was so young when she married Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines at the young age of 14 while he was 46. Her father, who was the Captain of the detached company that Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines was serving with, had most likely encouraged the marriage. While we do not know it with certainty, perhaps he encouraged the marriage because he knew the virtue and goodness of his fellow Officer, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines, and wanted his daughter to have a good husband such as him.

Last year – 2017 – marked the 250th anniversary of the death of Jean Baptiste François Tisserand DeMoncharvaux, the father of Elisabeth de Moncharvaux.

He was born on February 26, 1696 and baptized the same day in the Parish of St. Pierre, Diocese of Langres, in the north east of France, known as the Champagne region. After serving in the French Marines in Flanders and Canada, he was sent to serve in Louisiana, arriving in New Orleans on March 4, 1731.

He was first given command at the Post of Pointe Coupée, LA in 1731. (Interestingly, this is where his daughter, Elisabeth De Moncharvaux and her husband, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Vedrines would first settle after the French lost the War in 1763.)

He was first given command at the Post of Pointe Coupée, LA in 1731. (Interestingly, this is where his daughter, Elisabeth De Moncharvaux and her husband, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Vedrines would first settle after the French lost the War in 1763.)

The next year, in 1732, he was promoted to Enseigne en second and sent to Illinois in upper LA and put in charge of a small fort just erected at Cahokia in Upper LA (IL). At some point, he met Marie-Agnès Chassin (granddaughter of Marie Rouensa) and married her on February 11, 1737 at Kaskaskia, IL. (His first wife, Marie-Louise de Vienne and three sons had died in shipwreck on the way to meet him from Canada to IL).

From 1739-1748, he served as Commandant of the Arkansas Post near the mouth of the Arkansas River, where his daughter Elisabeth de Moncharvaux was born. In 1748, he was appointed Captain.

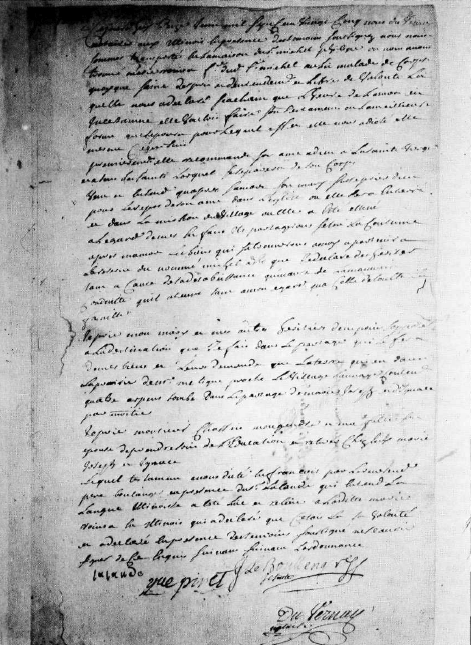

He was given command of the royal convoys up the Mississippi River from New Orleans, LA to the Illinois country in 1748 and 1749, during which he was accused of spending too much money and abusing alcohol but was later defended by Governor Vaudreuil (AN Col. C13 A35, f. 112).

In late 1751, he was commanding at the Kaskaskia Fort, where he was again in 1756, in command of a Company of 24 men (AN Col. D2, C51, f.24-28).

In 1757, he was stationed on the Missouri River along with his son, Jean Baptiste de Moncharvaux, Jr. and four other soliders (AN Col. D2, C51, f.24-28). (It was during this time that one of his Officers, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Vedrines, married his daughter, Elisabeth De Moncharvaux on October 10, 1758 at the chapel of St. Anne of Fort Chartres, IL.)

After the French loss the War in 1763, he returned to France. (See Robert Bruce Ardoin, Recueil de divers documents historiques et genealogiques relatifs aux families Vedrines et Tisserand, Puteaux, [France]: R. Uclaf, 1981, p. 24). (This was the same year his daughter Elisabeth de Moncharvaux and her husband, Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines moved to Lower LA at the Pointe Coupee Post.)

Jean Baptiste François Tisserand De Moncharvaux died four years after returning to France, on June 14, 1767 at the Hotel Dieu (Hospital), Paris. (One irony is that this is the oldest hospital in Paris, founded by the Bishop, St. Landry in 651. The same year De Moncharvaux died at the Hotel Dieu, his daughter and son-in-law and their children were living at the Opelousas Post in LA, which just a few years later would be known as St. Landry Parish.) Unfortunately the children of Jean Baptiste Lapaise and Elisabeth de Védrines were never able to meet neither their maternal or paternal grandparents.

More information about Jean Baptiste François Tisserand De Moncharvaux can be found in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

Elisabeth’s mother was Marie Agnes Chaisson, who was the daughter of Agnes Philippe. And Agnes was the daughter of Marie Rouensa “Aramepinchone” (1677-1725), a full-blooded Native American of the Illinois Kaskaskia tribe.

Originally from Peoria, the Kaskaskia Tribe first moved south to Cahokia (now a suburb of St. Louis, MO). Then, with the help of Jesuit Priests, they arrived at the mouth of the Kaskaskia River where it met the Mississippi River around 1703. Writing to a fellow Priest on November 9th, 1712, Fr. Pierre-Gabriel Marest, SJ, said: “The Illinois are much less barbarous than the other Indians…” In contrast to other tribes of Native Americans, Fr. Marest said that the Kaskaskia were “mild and affable” (J. F. Snyder, “The Kaskaskia Indians: A Tentative Hypothesis”, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984), Vol. 5, No. 2 (Jul., 1912), p. 236).

St. Louis, MO). Then, with the help of Jesuit Priests, they arrived at the mouth of the Kaskaskia River where it met the Mississippi River around 1703. Writing to a fellow Priest on November 9th, 1712, Fr. Pierre-Gabriel Marest, SJ, said: “The Illinois are much less barbarous than the other Indians…” In contrast to other tribes of Native Americans, Fr. Marest said that the Kaskaskia were “mild and affable” (J. F. Snyder, “The Kaskaskia Indians: A Tentative Hypothesis”, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984), Vol. 5, No. 2 (Jul., 1912), p. 236).

Marie Rouensa’s father was Chief Francois Xavier Mamentouensa Rouensa (1650-1725), who at one time served as Chief of the entire Illini Confederation.

Marie converted to Christianity shortly after the Jesuit Priests arrived in IL in the late 17th century and became an influential woman in their missionary work and in the village of Kaskaskia, IL. Her life was so significant that Duke University included her in their seminars on women who helped to shape the nation in 1999. Moreover, Ohio University teaches a history course based on her life, and the Illinois State Museum has an entire wing dedicated to Marie and her tribe.

Marie converted to Christianity shortly after the Jesuit Priests arrived in IL in the late 17th century and became an influential woman in their missionary work and in the village of Kaskaskia, IL. Her life was so significant that Duke University included her in their seminars on women who helped to shape the nation in 1999. Moreover, Ohio University teaches a history course based on her life, and the Illinois State Museum has an entire wing dedicated to Marie and her tribe.

The Jesuit Fr. Jacques Gravier, SJ described Marie’s conversion to Christianity at Peoria, IL probably in 1694, when she was 17 years old: “The girl made her First Communion on the feast of the Assumption of Our Lady; she had prepared herself for it during more than three months – with such fervor, that she seemed fully penetrated by that great mystery” (Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791, Cleveland: Burrows Brothers, 1896-1901, LXIV, 211-15).

Fr. Gravier’s letters also described with great enthusiasm Marie Rouensa’s prominent public role as a catechist. She became an important assistant who translated the teachings of the Christian faith into the language of the Illini Indians. Fr. Gravier says:

“This young woman who is only 17 years old, has so well remembered what I have said about each picture of the Old and New Testament that she explains each one singly, without trouble and without confusion, as well as I could do – and even more intelligently, in their manner. In fact, I allowed her to take away each picture after I had explained it in public, to refresh her memory in private. But she frequently repeated to me, on the spot, all that I has said about each picture; and not only did she explain them at home to her husband, to her father, to her mother, and to all the girls who went there, as she continues to do, speaking of nothing but the pictures or the catechism, but she also explained the pictures on the whole of the Old Testament to the old and the young men whom her father assembled in his dwelling” (Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791, Cleveland: Burrows Brothers, 1896-1901, LXIV, 211-15).

She was an instructor for the adults and children of her village of Kaskaskia and an interpreter who was recognized as a gifted storyteller. Even the elders came to hear her. Because of her generous and important help, Fr. Gravier was able to do go about doing his daily round of devotional duties while Marie drew new converts to his mission.

Some of her most important converts where her parents, Chief Rouensa and his wife.  Devotion to the Roman Catholic faith as it was conveyed to her by French Jesuit priests seems to have been a central element in Marie’s life from the time of her conversion in 1694 to the moment of her death. She continued to help the Jesuits in their work throughout her life, and when she died on June 25, 1725, she was buried beneath her pew in the parish church, the only woman in the history of Kaskaskia to have that honor. Her burial record states that at the time of her death at Kaskaskia in 1725, she was “about forty-five years old.” Her eight children ranged in age from 4 years old to 28 years old.

Devotion to the Roman Catholic faith as it was conveyed to her by French Jesuit priests seems to have been a central element in Marie’s life from the time of her conversion in 1694 to the moment of her death. She continued to help the Jesuits in their work throughout her life, and when she died on June 25, 1725, she was buried beneath her pew in the parish church, the only woman in the history of Kaskaskia to have that honor. Her burial record states that at the time of her death at Kaskaskia in 1725, she was “about forty-five years old.” Her eight children ranged in age from 4 years old to 28 years old.

Unfortunately, as a result of continuous wars with their northern neighbors, in particular the Sac and Fox Tribes, by the time of the Revolutionary War, the Confederation of Illini Native Americans had lost of most of its former territories and greatly decreased in number. In the fall of 1803, the Kaskaskia ceded all of their remaining lands in Illinois to the United States in return for protection and patronage. By the time of the War of 1812, most of the Kaskaskia moved west of the Mississippi to Missouri and Arkansas where they maintained their close relationship with the Peoria. In 1854, the Kaskaskia, Peoria, Piankeshaw and Wea Indians united into a single tribe or confederation called the Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma. The Tribal Headquarters are located in Miami, Oklahoma. (http://peoriatribe.com/history/kaskaskia-tribe/). One of the contemporary Chiefs of the Peoria Tribe with Kaskaskia heritage was Louis Myers. He passed away in 1994. Unfortunately, no more living Kaskaskia descendants are known except for the ones with mixed heritage like us (the Vidrine Family) who descend from Marie Rouensa.