275th Anniversary: Quartier dit du Baton Rouge

The Vidrine Family in LA celebrates the 275th anniversary of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ departure from France and arrival of LA in 2018. It’s a great time to remember and reflect on the 275 years of history of his descendants and the life and family he established in LA.

In his book about the Vidrine Family, Bruce Ardoin tells about a legend passed down in his family, told to him by one of his great uncles, Alfred Ardoin, who knew the Vidrine family very well. He says:

“A Vedrines and his wife came directly from France, and settled somewhere in the north of Ville Platte near Tate Cove. They had received a concession of land there. To be polite, and wishing to be accepted by those who lived there, Vedrine went to his nearest neighbor, about 4 miles from his home, to ask if settling so close did not disturb him. The neighbor, David Ardoin, grandfather of my great uncle replied that it didn’t!!! So they were accepted in the neighborhood. A few years later, one of the daughters of the Vedrine family wanted to marry a boy from Ville Platte. But, it did not please the father of the daughter, still she insisted, and she ended up marrying him. Sadly, her father disinherited her the same day in front of the doors of the church, while leaving the celebration of marriage. The date of this was around 1800 or so!” [English translation by Fr. Jason Vidrine](Robert Bruce Ardoin, Recueil de divers documents historiques et généalogiques relatifs aux familles Vedrines et Tisserand, Puteaux, France: R. Uclaf, 1981, p. 5).

Like all legends, there is both of bit of truth and a bit of untruth to this one. As we have seen in reflecting on the 275th anniversary of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ departure from France and arrival in LA, he was the first from the Védrines family in France to come to the new world. After a life of service in the French Marines in New Orleans and the pays des Illinois, he settled first at Pointe Coupée, and then at the Opelousas Post (present day Washington, LA), where he died and was buried.

It wasn’t until some time before 1796, that Jean Baptiste Lapaise and Elisabeth de Vedrines’ oldest son, Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine appears to have homesteaded land to the west of the Opelousas Post (Washington, LA) on the outskirts of the Prairie Mamou, at the place known as the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge (which would later be named Ville Platte). This land is considered Tate Cove today, so that part of the legend is correct. But, unlike the legend asserts, Pierre didn’t arrive at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge “directly from France” (he was born in IL and raised in LA). Nor did his wife, Marie-Joseph Brignac, who was born in Pointe Coupee and raised at the Opelousas Post.

It’s also difficult to know if the part about disowning his daughter after her wedding is true…and if so, to determine which daughter it would have been whose marriage might  have been objected to. Perhaps it was Pierre’s first daughter, Marie Celestine Vidrine, who married Elie Lucas Fontenot on February 10, 1812 (closest to 1800). It’s unlikely that it was his second daughter, Hyacinth Vidrine (b. 1794) who married Marcelin Garand (considered the founder of Ville Platte) on December 20, 1824 since it was further away from 1800 and, according to at least one account, Garand was accepted by Pierre Vidrine (See Claude-Alain Saby, 1815 Les naufragés de l’Empire aux Amériques, 2005, p. 253).

have been objected to. Perhaps it was Pierre’s first daughter, Marie Celestine Vidrine, who married Elie Lucas Fontenot on February 10, 1812 (closest to 1800). It’s unlikely that it was his second daughter, Hyacinth Vidrine (b. 1794) who married Marcelin Garand (considered the founder of Ville Platte) on December 20, 1824 since it was further away from 1800 and, according to at least one account, Garand was accepted by Pierre Vidrine (See Claude-Alain Saby, 1815 Les naufragés de l’Empire aux Amériques, 2005, p. 253).

Pierre’s younger brother, Etienne Vidrine dit Lapaise followed after him in September of 1796, settling on land next to his brother at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge, which he bought from his father in law, Noel Soileau. Etienne and Victoire’s first  born, Etienne Vidrine, Jr. was born on February 12, 1797 and baptized the same day. That same year on Christmas day, Jean Baptiste Pierre and Marie-Joseph’s fifth child and third son, Florentin Pierre Vidrine Sr., was born and baptized.

born, Etienne Vidrine, Jr. was born on February 12, 1797 and baptized the same day. That same year on Christmas day, Jean Baptiste Pierre and Marie-Joseph’s fifth child and third son, Florentin Pierre Vidrine Sr., was born and baptized.

About two years after Etienne Vidrine Jr. was born, Etienne Vidrine dit Lapaise’s second son, Zenon Vidrine Sr. was born on February 26, 1799. And two years later, his third son, Antoine Vidrine, was born in October 1801.

The Louisiana Purchase Treaty, in which Napoleon ceded the Louisiana Territory to the United States was signed in Paris on April 30, 1803. According to Article III, the “…inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be incorporated into the Union of the United States and admitted as soon as possible according to the principles of the Federal Constitution.” It took several years for it to happen, but on April 30, 1812, Louisiana finally entered the Union as the 18th state.

A few months after the LA Purchase, in October of 1803, Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine sold his land at the Opelousas Post and filed a land claim at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge (which was later named Ville Platte) in February of 1806 for the land he had homesteaded under the Spanish government before 1796. Also in 1803, Etienne sold the property he had purchased in 1796 next to his brother, Jean Baptiste Pierre at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge and moved to the south west of his former property, filing a land claim in June of 1807.

At this time – during the transition of the LA territory from Spain to the United States – Dr. Francois Robin observed:

“This country here, which a few years previously contained only savages, is inhabited with an infinite number of Frenchmen who are obliged to submit themselves to occupations of every kind in order to survive. This country is abounding in preceptors, teachers of dance, pack merchants, merchants of this and that. This country, which is rich due to its productivity, has just been ceded to the Americans. What will become of us in this new regime; these new morals and idioms, this religion, and all of the superiority that characterizes this Anglican nation? The only thing I can say is that Spain suffices for us” (David Lanclos, The letters of Dr. Franc̦ois Robin 1784-1826, 2009, p. 17).

We can imagine that Dr. Francois Robin’s sister-in-law, Madame de Védrines (Elisabeth de Moncharvaux) and her children had similar thoughts of what would come.

The move of both sons from the Quartier de l’Eglise (which would later be Washington) at the Opelousas Post where Jean Baptiste Lapaise and Elisabeth de Védrines had settled to the west at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge (which would later be Ville Platte) established that area as the new base of the Vidrine Family and their children.

The entire area around the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge on the outskirts of the Prairie Mamou (what today is Evangeline Parish) was a vacherie or grazing land for cattle for early French and Spanish settlers. By the late 1700s, colonization was well under way. Every year, huge roundups were held on this great open range. As pioneers homesteaded the area, property was divided and fences were built. With the settlement and development of the property, small towns sprang up and extended through this area. The Old Spanish Trail from Louisiana to Texas wound its way through this vacherie, which met the Spanish Trail from Florida to California. It came from the South of Opelousas and flowed northward through what is now Ville Platte, Bayou Chicot, then Alexandria, to Natchitoches, then on westward through Texas meeting the larger Spanish Trail near San Antonio. Some say that vestiges of this ancient, sunken road can still be seen off Highway 167 and in the Chicot State Park area.

In the same year that Louisiana was accepted as an American State, both of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Vedrines’ sons, like their father before them, proudly stood up to battle France’s ancient foe of England, but this time on behalf of the recently formed nation they  were now citizens of. The War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain would have a tremendous impact on the young country’s future. The United States suffered many difficult defeats at the hands of British, Canadian and Native American troops during the War of 1812, including the capture and burning of the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., in August 1814. However, American troops were able to overcome England’s invasions in New York, Baltimore and New Orleans. The war finally ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on February 17, 1815. Many in the United States celebrated the War of 1812 as a “second war of independence,” which helped to increase national confidence and to foster a new spirit of patriotism.

were now citizens of. The War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain would have a tremendous impact on the young country’s future. The United States suffered many difficult defeats at the hands of British, Canadian and Native American troops during the War of 1812, including the capture and burning of the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., in August 1814. However, American troops were able to overcome England’s invasions in New York, Baltimore and New Orleans. The war finally ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on February 17, 1815. Many in the United States celebrated the War of 1812 as a “second war of independence,” which helped to increase national confidence and to foster a new spirit of patriotism.

Both Jean Baptiste Pierre and Etienne Vidrine, dit Lapaise served in the War of 1812. Since Pierre was a little older than his brother Etienne, some of his sons were able to serve along with him, while Etienne’s children were too young. One interesting note is that we’re able to see that their lives were, in a sense, put on hold as they took up the call of duty. Pierre Vidrines’ daughter, Marie Elizabeth Vidrine was born in 1807…but his next child – his son, Andre Vidrine wasn’t born until August 1815 after the War was over. Likewise, Etienne’s son, Augustine Edouard Vidrine, Sr, was born just before Etienne left for the War (April 1812)…and his next child – his daughter, Victoire Irene Lapaise Vidrine was born just after the War finished (June 1815).

All members of the Vidrine Family who served are included in the list of LA soldiers in the War:

Vederine, Pierre Private 16 Reg’t. (Thompson’s), La. Mil.

[Most likely Pierre de Vedrines (1762-1830), son of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines and Elisabeth de Moncharvaux]

Vedrine, Dursite Private 16 Reg’t. (Thompson’s), La. Mil.

[Jean Baptiste dit Doisite Vidrine (1799-1845), son of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine and Marie-Josephe Brignac]

Vedrine, Florentine Private 16 Reg’t. (Thompson’s), La. Mil.

[Florentin Pierre Vidrine, Sr. (1797-1871), son of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine and Marie-Josephe Brignac]

Vedrine, Lapuse Private 16 Reg’t. (Thompson’s), La. Mil.

[Most likely Etienne Vidrine, dit Lapaise (1770-1849), son of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines and Elisabeth de Moncharvaux]

Vedrine, Pierre Private 16 Reg’t. (Thompson’s), La. Mil.

[Most likely Pierre Vidrine, Jr. (1790-1837), son of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine and Marie-Josephe Brignac]

We also find the husbands and sons of two of Jean Baptiste Lapaise de Védrines’ daughters:

Roza, Francois Private 16 Reg’t. (Thompson’s), La. Mil.

[Most likely Francois Roza (1783-1819), son of Saut Joseph Rosa and and Agnes Vidrine]

Rozat, Alexandre Private 16 Reg’t. (Thompson’s), La. Mil.

[Most likely Alexandre Joseph Roza (1781-1821), son of Saut Joseph Rosa and and Agnes Vidrine]

Fontenette, Charles Private Baker’s Regiment, La. Militia

[Most likely Charles dit Belair Fontenot (1758-1857), husband of Perrine Vidrine]

Fontenot, Lefroi Private 16 Reg’t. (Thompson’s), La. Mil.

[Maybe Leufroy Charlot Fontenot (1797-1862), son of Charles dit Belair Fontenot and Perrine Vidrine]

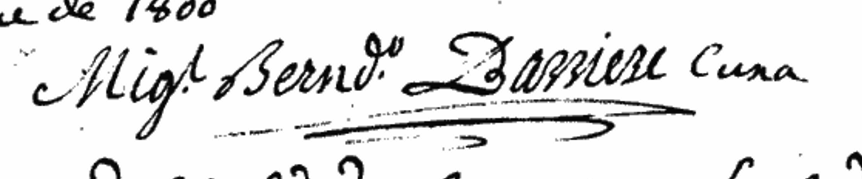

During the War of 1812, in 1813, Fr. Michel Bernard Barrière, an émigré Priest who fled the Revolution in France, was put in charge of St. Landry Church in the Opelousas area. As he had done a few years earlier at the Post of Attakapas to the south of the Post of Opelousas, he continued to saddle his horse for his missionary journeys throughout his parish, and these still occasionally presented extreme difficulties. Fr. Barrière gives us an insight into transportation on the Opelousas Prairie in a note he made in the sacramental register of St. Landry Church. While one of his parishioners on the prairie was dying, “he could not receive the Sacraments due to the high water which flooded everywhere because of the abundant rains which we’ve received for over a month and the lack of bridges” (See St. Landry Death Register, V.1, p. 138).

According to the Baptismal records, in which Fr. Barrière is well known to have provided so many details, he went on a missionary excursion during the month of November 1813, celebrating at least eighteen baptisms. He traveled through the “Prairie Mamou,” to James Campbell’s, then to Mrs. Hall’s, then again to Dennis McDaniel’s at the head of “Bayou Chicot”, then to the “Quartier called Baton Rouge” at the house of “Mr. [Jean] Baptiste de Vidrinne” and finally at Pierre Foret’s, in the “Prairie Ronde” ( Historical Sketch of the Parish of Opelousas, LA, Rev. Charles Souvay, C.M., Saint Louis Catholic Historical Review, Volumes 2-3, (St. Louis, MO: 1920), p. 246; See also St. Landry Baptism Register, Volume 2, p18).

We know for sure that Fr. Barrière was at the home of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine on November 18, 1813. As he notes in the Sacramental Records, it was during a mission “Dans le quartier dit du Baton Rouge chez Mr. Baptiste de Vidrinne” [in the area called

Baton Rouge at Mr. Baptiste de Vidrinne] on November 18, 1813 that he baptized Celeste McDonald (daughter of John McDaniel, Sr. and Catherine Corkran), Damasena Ortego (daughter of Jean Francois Ortego and Eugenie Fontenau), and Margarita Ortego (daughter of Joseph Gregoire Ortego and Emelie Fontenau). During this same time, Fr. Barrière encountered the matron of the Vidrine family in Louisiana, Elisabeth de Monchervaux, who was now living with and receiving care during her sickness from her son Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge.

Baton Rouge at Mr. Baptiste de Vidrinne] on November 18, 1813 that he baptized Celeste McDonald (daughter of John McDaniel, Sr. and Catherine Corkran), Damasena Ortego (daughter of Jean Francois Ortego and Eugenie Fontenau), and Margarita Ortego (daughter of Joseph Gregoire Ortego and Emelie Fontenau). During this same time, Fr. Barrière encountered the matron of the Vidrine family in Louisiana, Elisabeth de Monchervaux, who was now living with and receiving care during her sickness from her son Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge.

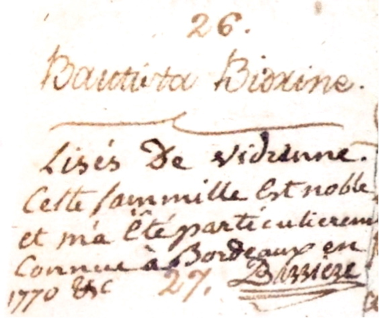

It’s not surprising that Fr. Barrière was at the home of Jean Baptiste Pierre Vidrine where he celebrated the Sacraments on his missionary journey through the Opelousas Prairie considering an interesting note he made in the Sacramental records. As was stated, he is well known for his various notes in the margins of the Sacramental records, in which he expressed strong memories and feelings as he went through the parish records. In the first Baptismal register of St. Landry Church, there’s a note made in the margin next to the entry about Jean Pierre Baptiste Vidrine’s second son, Lisandre Jean Baptiste Vidrine, who had been baptized by Fr. Pedro de Zamora in August of 1791. The Spanish Capuchin had recorded the name as he had most likely heard it – incorrectly – as Bidrine. When he went through the registers as the Pastor years later, Fr. Barrière corrected it by noting that it was actually de Vidrenne (Védrines), and that he had known the family well in Bordeaux in 1770.

expressed strong memories and feelings as he went through the parish records. In the first Baptismal register of St. Landry Church, there’s a note made in the margin next to the entry about Jean Pierre Baptiste Vidrine’s second son, Lisandre Jean Baptiste Vidrine, who had been baptized by Fr. Pedro de Zamora in August of 1791. The Spanish Capuchin had recorded the name as he had most likely heard it – incorrectly – as Bidrine. When he went through the registers as the Pastor years later, Fr. Barrière corrected it by noting that it was actually de Vidrenne (Védrines), and that he had known the family well in Bordeaux in 1770.

Writing to his family in France from Opelousas on May 6, 1815, Dr. Francois Robin mentions Elisabeth de Moncharvaux as the sister of his wife who had died (his sister-in-law) and that Elisabeth was one of the few heirs of Jean Baptiste Francois Tisserand de Moncharvaux still remaining (David Lanclos, The letters of Dr. Franc̦ois Robin 1784-1826, 2009, p. 29).

In that same letter, Dr. Francois Robin wrote: “The scourge of the war [War of 1812] was not very noticeable. My four sons were called to serve, the eldest in the rank of Captain, and the three others as soldiers. Fortunately, they all returned after having participated in the defeat of the English on January 8th of this year” (David Lanclos, The letters of Dr. Franc̦ois Robin 1784-1826, 2009, p. 27).

The next spring, Elisabeth de Monchervaux, turned 72, and by that fall, she passed away. Fr. Barrière notes in the record of her death and burial that she spent “three long years” at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge “on the outskirts of the Mamou Prairie” [in the care of her son Pierre Vidrine] before dying there on September 6, 1816. She was buried at the cemetery of St. Landry Church in Opelousas (V.1, p.155). Sadly, though, her tomb can no longer be found.

Referring to his residence along Bayou Teche, Dr. Francois Robin wrote: “It is a beautiful property and in France is would be considered of great value. I can only thank Providence for the state in which I find myself. I don’ t have a fortune, but I have need of no one. The wealth I have accumulated would be a fortune in any other country…” (David Lanclos, The letters of Dr. Franc̦ois Robin 1784-1826, 2009, p. 27). The Vidrine brothers most likely shared similar sentiments about their settlement and life established at the Quartier dit du Baton Rouge.

Finally, in a letter to his cousin in the fall of 1818, Dr. Francois Robin gives us a glimpse of life throughout the Opelousas territory in the aftermath of the War of 1812 and the reality of the State of Louisiana’s acceptance into the Union:

“Land has increased a hundred fold in value during the last few years. This

vast country, which had at the most 800 to 1000 inhabitants upon my arrival [in 1786], is now comprised of 12 to 15 thousand. Commerce is very brisk and everyone is involved in it. The Americans have thrust us out of our lethargy, and before our eyes were completely open, those that set an example for us (having only their skills) became rich before we did. One cannot explain the inclination of the Americans to educate themselves. The least of them go barefooted, know how to read, write and calculate, and are knowledgeable of the laws of the United States. They have land, have seen practically all there is to see, and have acquired several positions or professions” (David Lanclos, The letters of Dr. Franc̦ois Robin 1784-1826, 2009, p.54).

There’s no doubt that much of the French identity, culture, and way of life of members of the Vidrine Family has endured even hundreds of years later. I remember my paternal grandfather in the early 2,000’s pointing north and saying “Ça c’est les Americains” in reference to those who lived about 15 or 20 miles north of his house just outside of Ville Platte. Nevertheless, there’s also no doubt that from this time on – with both parents having passed away and the American life and spirit deeply influencing their experience – the transition from Vedrines to Vidrine had truly begun. Up until this time, both ways of spelling the name could be found in sacramental and civil records. But from this time on, it’s almost exclusively written as Vidrine.